Projects and Features

In the post

A former Royal Mail sorting office is being reconfigured into a new mixed-use development with large areas of the original steel structure being retained. Martin Cooper reports.

A former Royal Mail sorting office is being reconfigured into a new mixed-use development with large areas of the original steel structure being retained. Martin Cooper reports.

FACT FILE

The Post Building, London

Main Client: Brockton Capital and Oxford Properties

Architect: Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

Main contractor: Laing O’Rourke

Structural engineer: Arup

Steelwork contractor: BHC

Steel tonnage: 4,700tHaving stood as a derelict structure for more than 20 years, the former Royal Mail sorting office on London’s New Oxford Street is being brought back to life as a new mixed-use development containing commercial, retail and residential elements.

Occupying a prominent West End site, the scheme will not only reinvigorate the plot, it will also create a desirable building close to many amenities and public transport links.

Main contractor Laing O’Rourke [LOR] started work on site in late 2016, initially undertaking a large-scale demolition programme. Unlike many other city centre schemes, this demolition project also included retaining a large portion of the original 1960s-built steel-framed building.

Therefore, a horseshoe-shaped zone in the middle of the site containing ground, first and second floor levels was left in place. These floors were originally used for mail sorting duties, while the building’s upper four floors, now demolished, accommodated administrative offices and a plant level.

“It’s all about gaining planning permission and getting the most efficient use of the existing structure,” explains LOR Project Manager Andrew Veness.

“The retained element has high floor-to-ceiling heights and so we’ve been able to insert three mezzanines and consequently add more office space.”

How the steel erection looked last May

The completed building’s New Oxford Street façade

The project’s upper floors nearing completion

Keeping some of the original steel frame also fitted into the overall design aesthetic, which will ultimately see the new building have exposed steel beams and columns creating a modern ‘white collar factory’ office building.

Retaining a large steel frame required steelwork contractor BHC to use more than 200t of temporary steel propping and bracing, as the frame’s original stability system had been demolished. The stability system was completely remodelled to remove the existing cores from the key corner floor areas and create a new one in the central part of the site.

Careful consideration of the sequence of work and load transfer was required. Temporary works were also needed to permit the construction of the new frame over existing live network substations, which could not be moved prior to erection commencing.

“Once the temporary props were in place we then set about constructing a new central core that sits within the open end of the retained structure’s horseshoe shape,” says BHC Project Manager Bobby McCormick.

Once the steel core was erected, the retained steelwork was connected to this new stability-giving element and this then allowed the temporary props and bracing to be dismantled.

A number of factors came into play when the design team chose a steel core instead of a concrete one. The site’s basement and raft foundations have both been reused and a lighter steel option helped avoid the need for new piles.

“As well as the steel option being lighter, it was also deemed to be in keeping with the desired overall design aesthetic of exposed steelwork throughout the building,” explains Arup Project Engineer Tim Bennett.

“The former post office underground railway runs directly beneath the site and so it was also important not to add unnecessary loads.”

Having stabilised the retained steelwork BHC then set about reconfiguring the large steel beams in readiness for the insertion of new steel mezzanine levels.

The original grid pattern for the Post Building’s ground floors was 12m × 20m to suit post office vehicle movements. Consequently, a series of deep transfer beams was originally installed to support these spans. These transfer beams had the effect of concentrating the original building loads into heavily-loaded, widely-spaced points on the raft foundation.

As the ground floor is no longer subject to vehicle movements, the very long spans over this area are no longer necessary. As such, by providing new columns to cut down the long spans, the increased overall building mass can be spread more evenly on the existing foundations.

By removing the transfer beams’ concentrating effects, the widely-spaced high point loads are replaced by more frequent, lower point loads. This helps limit punching shear and bending forces within the raft, such that the increased building size can be carried.

The now redundant transfer beams have been slimmed down from 1.8m-deep to 500mm-deep members. This involved a large amount of site modifications to the existing plate girders, with a large team of welders on-site.

Where mezzanine floors have been inserted, the existing steel beams have been trimmed to maximize available headroom within the existing floor-to-floor heights.

An entirely new steel frame has been erected around the retained portion completing the lower three floors and filling up the entire site’s footprint. At the south east corner of the site a new residential zone has been created and integrated within the overall structural footprint.

Elements of the retained building were integrated at levels one, two and three, and this dictates the floor-to-floor height of these storeys. Above this, new construction is provided following the original grid at levels four and five.

These floors step-in at levels five and eight, where transfer beams have been installed to support the column location changes. Substantial transfer structures were included at level five to permit the upper floors to follow a more attractive spatial planning grid

Level eight also has a slightly higher floor-to-ceiling height than the other new floors and includes another mezzanine. The roof profile has been stepped back to minimise visual intrusion, and trusses spanning along the step lines have been used to reduce the number of internal columns, maximising clear internal floor space.

“This is a very challenging project and site, with lots of trades working simultaneously, all of which has required a good deal of coordination,” sums up Mr Veness.

“Retaining and altering the old steelwork was an engineering feat requiring the frame to be surveyed throughout the works. We also found the old steel to be in good condition, in some ways due to it being coated in lead paint, all of which had to be carefully removed.”

In total, the mixed-use development creates 44,000m² of floorspace, with eight floors of offices and seven floors of adjacent residential (including 100% of the required affordable housing provision on-site) above two floors and a basement containing a variety of public uses including shops, cafés, galleries, and a GP surgery for the local community.

The development also makes a significant contribution to the public realm by creating a new public space on Museum Street, reactivating the historic route of Dunn’s Passage, and providing a public roof terrace.

The Post Building is scheduled to complete by December 2018.

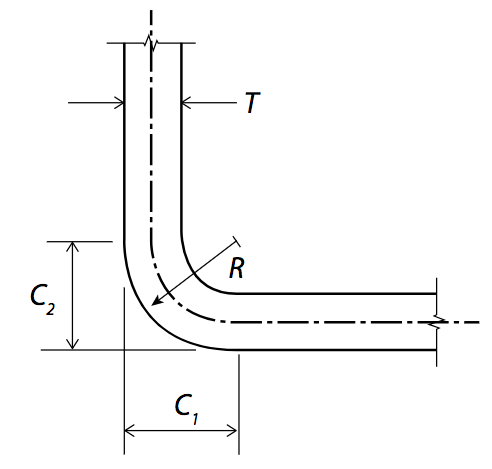

Modifying existing frames

Significant modifications to the existing steel frame are a key feature of the work to reconfigure the Post Building. David Brown of the SCI discusses some of the issues with refurbishment projects.

One of the existing transfer beams that was reduced in depth from 1.8m to 500mm

The first concern is always to discover details of the existing structure, which will often demand site investigation – it is very uncommon to find sufficient drawings to describe the structure, and even less likely that design calculations are available. Comprehensive surveys are needed, recognising that modifications through the years may have been undertaken with no records at all. Assessment of the existing structure must follow, acknowledging the design Standards and material quality of the time.

At the Post Building, significant site fabrication and welding was undertaken to reduce the depth of the existing transfer beams. For any form of welding, procedures must be developed and followed to minimise the risk of defects, which in turn demands that the composition of the original material be known. Site welding sometimes carries with it the idea of slightly shoddy work, but this should not be the case. Site welding should be completed to the same demanding standards of shop welding, involving weld procedures, qualified welders and post weld inspection.

Another feature of the refurbishment of the Post Building is the change in loading regime for many members. Design forces have been modified, in phases, and the resistance of the member must be carefully considered at each stage. Additional steel reinforcement to increase member resistance will not carry the stress from the existing loads, unless some form of jacking is undertaken to temporarily relieve the member. Unless the existing load is relieved, the stress in the original member must be considered in the verification of any site-fabricated compound members.

The Post Building is also notable for the complete remodelling of the building’s stability system and the careful thought required to transfer the loads and to develop the temporary works requirements. Stability is of fundamental importance to the structure, addressed under the CDM regulations and the National Structural Steelwork Specification. The NSSS calls for an outline of the method of erection envisaged by the structural designer, together with information on the assumed temporary works and the erection stage when the temporary works are no longer necessary.

Designers undertaking refurbishment or adapting existing structures will find the first reference particularly helpful, as it provides guidance on historic steelwork, but also on the principles to be followed when working on the modification of structures of any age.

Appraisal of existing iron and steel structures, P138, SCI

Appraisal of steel structures, SN41, Steelbiz

Guide to site welding, P161, SCI

National Structural Steelwork Specification, 6th edition, BCSA