Projects and Features

United States can learn from worldwide fire engineering expertise

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology makes 30 recommendations to improve the safety of tall buildings in its report on the collapse of the World Trade Center. But, in the second of a series, John Dowling reports that NIST appears reluctant to accept experience from outside the US regarding performance-based fire design.

After nearly three years of research, the draft of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) report into the collapse of the World Trade Center towers was released in June of this year. Readers were invited to submit comments by early August and the final report was issued to coincide with a seminar at NIST headquarters in Maryland in mid-September. The report deals specifically with the collapse of the twin towers and the recommendations are explicitly aimed at tall buildings, defined as taller than 20 storeys, and buildings of special risk.

NIST has used the launch of the report to call on the organisations that develop building and fire safety codes, standards and practices — and the state and local agencies that adopt them — to make specific changes to improve the safety of tall buildings, their occupants and emergency services. The report, which incorporates the results of 43 detailed technical investigations, makes 30 recommendations divided into eight groups (see box).

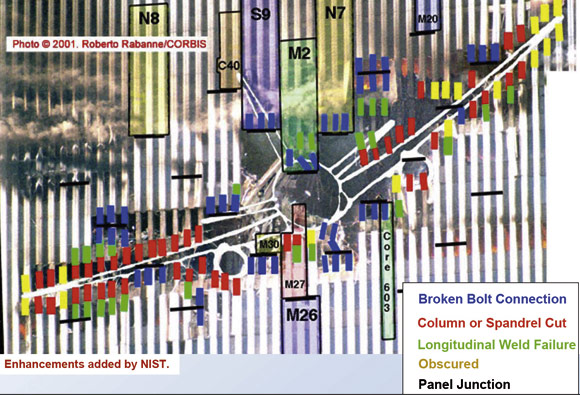

From the point of view of the steel construction sector, the report makes a number of positive statements, including: “The WTC towers likely would not have collapsed under the combined effects of aircraft impact damage and extensive multifloor fires if the thermal insulation had not been widely dislodged by impact.” This supports previous statements from the research team which had pointed to the excellent performance of the structure after the impacts.

The report states that at the time of impact, the towers contained 17,400 occupants, spread almost evenly between the two. Some 87% of occupants, including over 99% of those below the impact points, were able to escape. The reports concludes that “…for those seeking and able to reach and use undamaged exits and stairways, the egress capacity was sufficient to accommodate survivors.”

The big message, however, is that “a full capacity evacuation of each tower with 25000 people… would have required about four hours. Had the buildings been full, it is possible that as many as 14,000 people could have lost their lives… the egress capacity required by current building codes and practice is based on phased evacuation strategy, not full evacuation.” Survivors moved much more slowly than in previous non-emergency evacuations and fire brigade personnel had difficulty getting up the stairs due to the counterflow. This has led to recommendations for full building evacuation in tall buildings and the use of protected/hardened elevators.

It is this issue which is likely to have the most immediate impact on tall building design and the effect is already being seen in proposed changes to Building Regulations Approved Document B (the most widely used source of information on fire safety requirements in England and Wales). The proposal, which the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister acknowledges has been inspired by research into the World Trade Center collapse, and which it is intended will apply to buildings over 30m in height, will result in wider stairs. The increases would vary from 70 to 1400mm but would typically be about 300 to 400mm.

NIST encourages owners, designers and regulators to consider the recommendations and “take steps to mitigate unwarranted risks without waiting for changes to occur in standards and practice”. However, until more detailed guidance is available, it is likely that these recommendations will be used mainly as guidance in risk-based approaches on specific buildings.

Only two of the eight sets of recommendations have implications for structural design. Those under the heading of increased structural integrity call for the prevention of structural collapse. In a recent article, Faith Wainwright of Arup (The Structural Engineer, 19 July) writes, “Clearly in the UK we are somewhat ahead in having a basic requirement to design against progressive collapse. However, with a new call for guidance, there should be increased impetus to consider how collapsing structures cater for the large deformations which result — this is not covered in the UK. Imperial College is currently researching the development of simple guidance for steel structures… once this is understood, the interaction with fire needs to be taken into account. The NIST call for development is therefore welcome.”

Under the heading of new methods for fire resistant design of structures, the report carries four specific recommendations. The most interesting of these occurs where NIST recommends the development of “performance-based standards and code provisions, as an alternative to current prescriptive design methods, to enable the design and retrofit of structures to resist real building fire conditions, including the ability to achieve the performance objective of burnout without structural or local floor collapse and the development of tools, guidelines and test methods necessary to evaluate the fire performance of the structure as a whole system.” The report goes into considerable detail as to the amount of research and development which is required before the tools and methods are available to enable this type of analysis to be carried out. This was picked up in an article in New Civil Engineer shortly after the publication of the report which said that there was to be “no further use of performance-based fire design until more research is completed”. The report contained no such quote in its text or recommendations.

Although the tenor of the recommendations is strongly supportive of performance-based approaches to fire engineering design — and very logically, since such approaches provide a much better understanding of how real structures behave in fire and therefore give a much clearer indication of real safety levels than traditional prescriptive methods — the nature of the recommendation is disappointing. It points to a significant weakness of the work which has been carried out by NIST: the apparent refusal to accept that anything could be learned from the experience and knowledge of researchers and practitioners outside the US. In the UK, performance-based methods have been in widespread use for some years and leading consultancies such as Arup Fire and Buro Happold Fedra as well as the Universities of Sheffield and Edinburgh, among others, have considerable expertise in this area. It is hoped that NIST does not reinvent the wheel.

The Report’s Recommendations

Increased Structural Integrity

The standards for estimating the load effects of potential hazards (such as progressive collapse, wind) and the design of structural systems to mitigate the effects of those hazards should be improved to enhance structural integrity.

Enhanced Fire Resistance of Structures

The procedures and practices used to ensure the fire resistance of structures should be enhanced by improving the technical basis for construction classifications and fire resistance ratings; improving the technical basis for standard fire resistance testing methods; using the “structural frame” approach to fire resistance ratings; and developing in-service performance requirements and conformance criteria for spray-applied fire resistive materials (the WTC Towers were fire protected using this type of material).

New Methods for Fire Resistance Design of Structures

The procedures and practices used in the design of structures for fire resistance should be enhanced by requiring an objective that uncontrolled fires result in burnout without local or global collapse. Performance-based methods are an alternative to prescriptive design methods.

Active Fire Protection

Active fire protection systems (sprinklers, standpipes/hoses, fire alarms and smoke management systems) should be enhanced through improvements to design, performance, reliability and redundancy of such systems.

Improved Building Evacuation

The process of evacuating a building should be improved to include system designs that facilitate safe and rapid egress; methods for ensuring clear and timely emergency communications to occupants; better occupant preparedness for evacuation during emergencies and incorporation of appropriate egress technologies.

Improved Emergency Response

Technologies and procedures for emergency response should be improved to enable better access to buildings and more effective response operations, emergency communications, and command and control in large-scale emergencies.

Improved Procedures and Practices

The procedures and practices used in the design, construction, maintenance, and operation of buildings should be improved to include encouraging code compliance by non-governmental and quasi-governmental entities; adoption and application of egress and sprinkler requirements in codes for existing buildings; and retention and availability of building documents over the life of a building.

Education and Training

The professional skills of building and fire safety professionals should be upgraded through a national education and training effort for fire protection engineers, structural engineers and architects.