Projects and Features

Wilkinson at steel’s cutting edge

One of the best known names in UK architecture, whose international repute is growing strongly with ambitious and high profile projects under way worldwide, is Wilkinson Eyre. Founder Chris Wilkinson tells Nick Barrett about some of his firm’s major successes with steel construction.

Chris Wilkinson is one of a relative handful of architects who comfortably occupy that space between architecture and engineering from where designs of many of the iconic steel structures of our age emerge. The relationship between structural engineering and architecture has become ever more symbiotic over recent years, thanks partly to the attitudes and vision of architects like Chris Wilkinson and the constantly expanding possibilities afforded by steel as a construction material.

Architects have often led the way, with their vision creating new challenges for structural engineers and steelwork contractors to rise to. Architects in turn have been inspired by the new possibilities provided by advances in steel construction. With success more architects see the potential for designing in steel and another raft of new challenges soon arises.

Many of the challenges are coming from the Smithfield area of London, where Wilkinson Eyre has its headquarters across the road from another innovative leader Zaha Hadid. CZWG and other well known architectural names are nearby and the area is becoming a bit like an architectural equivalent of what Victoria once was for consulting engineers.

The recently completed Shard is framed by a picture window at Wilkinson Eyre’s office, and Chris Wilkinson generously agrees that he likes and is impressed by the structure designed by Renzo Piano. “It is a striking addition to the London skyline and is a bold design.”

Wilkinson Eyre is one of those practices that values designs that embrace the structural form, equal weight being given to creative innovation at the conceptual stage and to technical design. A frequently heard idea when talking to Chris and others in the practice is to allow the structure to be expressed. But Chris denies there is any house style: “We are pragmatic and realise that particular problems demand their own solutions, rather than having any house style imposed on them.”

Full credit is also given to the contributions of structural engineers: “An interest in and knowledge of engineering on behalf of architects leads to good collaborations,” says Chris. “We understand structures, which enables us to work closely with engineers and specialise in unusual and specialised projects. Because of that understanding what we design is what is built.”

The emphasis is on innovation, always looking for new ways to do things, as the track record proves. “We are always pushing technology.”

The practice, founded in 1983 by Chris and later joined by Jim Eyre, is perhaps best known to the public for the Gateshead Millennium Bridge and the Magna Science Adventure Centre, created from a disused steelworks in Rotherham, both RIBA Stirling Prize winners. Some of its projects are truly iconic, such as the Millennium Bridge, and one has appeared on a postage stamp and one on a one pound coin.

For the London 2012 Olympics the firm designed the Basketball Arena and the Emirates Air Line cable car over the Thames. In Singapore, the just completed Gardens by the Bay involves a pair of steel framed large glasshouses, the larger of the two being 200m by 100m, similar in concept to the UK’s Eden Centre but using glass rather than ETFE. It creates a Mediterranean climate inside the glasshouses to allow cultivation of flowers and shrubs that would not otherwise grow in the local, tropical climate.

Wilkinson Eyre’s £600M Guangzhou International Finance Centre is now in occupation and has been selected for the shortlist of this year’s RIBA Lubetkin Prize, which is awarded to the best new building outside the European Union. Relatively little has been heard in the UK about this composite, concrete filled steel framed giant, but it is the tallest tower in the world by a UK architect.

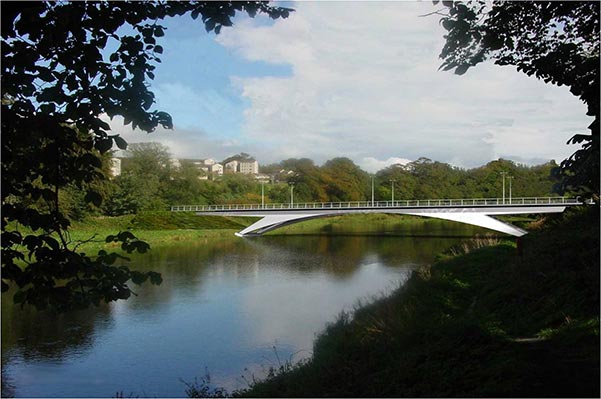

Wilkinson Eyre regularly features in the Structural Steel Design Awards, winning two Awards this year, for the Footbridge at MediaCityUK spanning the Manchester Ship Canal, and for the Peace Bridge spanning the Foyle in Derry-Londonderry. “Despite the awards our bridges win, bridges only account for about 10% of our workload,” says Chris. “We enjoy designing them but buildings and other structures provide the bulk of our work.”

A previous SSDA winner, in 2011, which well illustrates Wilkinson Eyre’s approach, was the 17,000m2 Audi Centre adjacent to the M4 elevated section in London, said to be the world’s largest Audi showroom. Also serving as Audi’s UK headquarters, the striking seven storey design takes inspiration from nature, art and science, with sweeping curves in the roof said to be reminiscent of a manta ray fish and the wings of a stealth fighter aircraft. The science in this light filled building is partly in the steel frame, and in innovations like the rods raking from a first floor slab that support a 70m wide mezzanine floor.

Steel obviously features very strongly in Wilkinson Eyre’s project portfolio and Chris admits: “We do like steel as a construction material, for a number of reasons. We will always choose the appropriate material for the job, and that has often meant steel has been preferred. We like it because it is lighter and quicker to construct. Because it is fabricated some quality issues are taken away and it gives us more opportunities in design, to shape and form the structure.

“Projects like the Dyson headquarters, which is basically a big shed, showed us early on as a practice how flexible steel could be, as we are seeing now with the demountable and temporary Olympic structures. There will be a lot more demountability in future which will mean more structures taking advantage of this flexibility.” The Dyson headquarters was completed in 1999 and is currently being reconfigured having already been extended once.

The outlook is improving for workloads, especially overseas, although Chris admits that the last six months have been tougher in the UK as a lot of large projects are taking a long time to come through. Work in China is growing, and projects are under way in Singapore, Australia, Denmark and Germany. The practice is now among the top 50 UK architects, with about a third of income of over £10 million derived from overseas.

Recession hit numbers of architects employed but there has been a good recovery since then and the UK offices now employ 110. “We are active in a lot of different sectors and in a lot of countries and this spread helps when economic times are harder,” says Chris. “We were fairly stable during the recession although we lost about 10% of staff when things looked bad in 2008. We were back up within six months and we are still growing.”

Guangzhou International Financial Centre

Guangzhou International Financial Centre

At 440m high this is one of the tallest buildings in China and the 10th tallest in the world, half as big again as London’s Shard. The 103 storey composite structure provides 247,000m² of mostly office and hotel space. It is said to be the world’s tallest diagrid, designed with Arup.

It employs 50m high diagrid tubes of two metre diameter which taper to 1.2m. It has a triangular form with double curved elevations. The diagrid structure around the building’s perimeter enabled an economical steel design. Photo © Christian Richter

Stratford Market Depot

Stratford Market Depot

This was a key project for the practice, won with Acer, now Hyder. This is a true ‘Supershed’ as defined in his book ‘Supersheds’ which was first published in 1991, a 200m by 100m train depot, shortlisted for the Stirling Prize. “This was a turning point for us,” remembers Chris. ‘”It was won in a competition which was good as we hadn’t done a big shed before. It was engineer led, and on the critical path for the Jubilee Line.

“We were able to do what we thought was appropriate for the brief and our design fully expressed the structure.”

Its diagrid structure was dictated by the railway track alignment. Clear spans were not a key requirement so the structure is described as hybrid. “It is an economical structure with large trusses supported on V columns, a fairly new approach for supporting horizontal loads at the time,” says Director Oliver Tyler. “There were only five in the practice when I joined and I cut my teeth on this project. It is a simple structure with beautiful internal spaces, fully glazed at one end.”

Photo © Denis Gilbert, View

Gateshead Millennium Bridge

Gateshead Millennium Bridge

Type Gateshead into Google and the first item up is Gateshead Millennium Bridge. This Stirling Prize winning, landmark, tilting bridge, is the last of a run of five bridges won in competition, this time with Gifford. It is internationally recognised for its unique and innovative design, the best known feature of which is its rotating deck. It was also awarded the IStructE Supreme Award and there is a page full of awards for its design and lighting listed on the bridge’s own website.

Not perhaps the bridge’s greatest claim to fame is the fact that it appears on a Newcastle Brown beer label. “It has become a spectacle,” says Chris, “and appearing on a Newcastle Brown label is probably as great a sign of local recognition that there is.

”They open it when it doesn’t need to be opened just so that it can be seen by people who have often travelled just to see the bridge. “ Chris still speaks of the bridge as if he is in still in some awe himself of what was created. “It was placed into position in only half a day, which itself was quite an achievement.”

Photo © Graeme Peacock

Stratford Station

Stratford Station

This is another Stirling Prize shortlisted building, where the same philosophy of expression of structure is seen as at Stratford Market Depot. This was an early public building for the practice, which acts like a terminus for the Jubilee Line above ground. “This was one of the first of what was to be a long run of major new projects for the East End of London, which had been neglected for many years,” says Chris.

It is a stainless steel clad modular building, only two 30m bays originally, but funding for a third bay was found later. Trusses span 30m across the railway tracks. “It is a very elegant and efficient design employing passive ventilation. Working closely with the structural engineer we were able to make the structure very expressive.”

The design includes a propped cantilever bolted down to ‘gattling gun’ nodes that Chris describes as ‘beautiful castings’. A lot of bolts were expressed in this design. A lot of time was invested in exploring the use of elliptical tubes on this structure to form what are basically elliptical boxes. There are no services running in the soffits, with the base of the trusses being used for maintenance walkways and services.

Chris says: “There was a recession on at the time so we had time to do some research, something that we struggle to be allowed to do now.”

Photo © Dennis Gilbert, View

South Quay Footbridge

South Quay Footbridge

Wilkinson Eyre is renowned for bridge designs and this one between South Quay Plaza and Heron Quays at Canary Wharf in London’s docklands was its first. It was also the first of a series of wins in bridge design competitions. “We won five in a row,” Chris recalls. “We had a new way of looking at structures that resulted in very attractive, innovative bridges that pleased clients and bridge users.”

South Quay is a 180m long cable stayed structure, designed in cooperation with Jan Bobrowski. One of the original twin spans opened for shipping, and it was designed to allow for the fixed span being removed later for use elsewhere as Canary Wharf development progressed and a dock was partly infilled. The southern 90m span was eventually swung into a new orientation.

Photo © Wilkinson Eyre