Projects and Features

University challenge

The ‘floating glass box’ of the ziggurat’s upper level is hung from the hangar’s original green steelwork

Forming part of a new campus extension, a three storey steel structure, dubbed the ziggurat, has been inserted inside a former aircraft hangar. Martin Cooper reports from Cranfield University.

FACT FILE: Vincent Building, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire

Main client: Cranfield University

Architect: Sheppard Robson

Main contractor: Haymills

Structural engineer: Scott White Hookins

Steelwork contractor: Midland Steel Structures

Steel tonnage: 110t

Located deep in the Bedfordshire countryside Cranfield is a renowned postgraduate university for aeronautics and advanced technology. Housed on a former RAF airfield used during the Battle of Britain, Cranfield’s collection of buildings – some of which were left by the air force – has recently been added to by a structure very much of this century.

The Vincent Building is a new four-storey, fully glazed and contemporary laboratory block designed by Sheppard Robson. Adjoining the back elevation of this building, a steel-framed atrium has been constructed which then links the new building to an existing hangar which was previously used as a sports hall.

The north east corner of this hangar, representing about an eighth of the structure, has been converted with the insertion of a new three-storey administration structure spanning a ground floor lecture theatre.

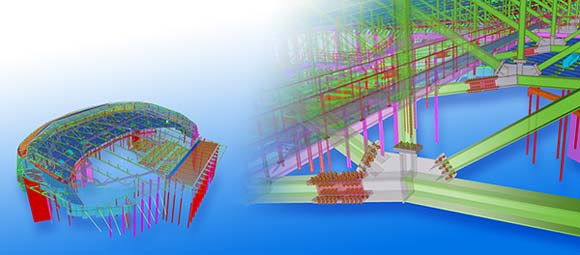

This steel-framed building within a building has been dubbed ‘a ziggurat’ by Sheppard Robson and all three of its floors have an individual layout which allows natural daylight to penetrate down into them from all sides. The irregular configuration also means there are open terraces on the upper two floors of the ziggurat which serve as break-out areas for members of staff.

The ‘floating glass box’ of the ziggurat’s upper level is hung from the hangar’s original green steelwork

As Jason Daniels, Engineer for Scott White Hookins, explains: “The concept for the three-storey structure was for varying floor plans to give the entire area an open plan feel.” Consequently, no supporting columns in the ziggurat line up as each floor plate is at a different angle.

There are not too many columns within the upper two floors as the design concept required a column free floorspace. However, structurally the second floor had to have two internal columns in full view, while the majority have been secreted into perimeter walls. The ziggurat is also free-standing and stability is derived from a braced frame, with bracing again secreted in walls.

The three-storey ziggurat has fully glazed partition walls, but these too are set at a slight angle on plan to the adjacent rectangular laboratory block. Where the upper two levels step back, their glazed perimeter walls are also set at different angles.

“There are no internal columns in the upper floor as the rooms are completely open plan,” adds Mr Daniels. “The design concept here was for an open glass box which gives the impression that it’s floating.”

The floor of the upper level of the ziggurat is supported from the floor below, while the roof of this ‘glass box’ is actually hung from a series of steel trusses which form the roof of the original hangar. Painted a vivid lime green, this complex web of beams and ties are clearly visible as new rooflights have been inserted into the hangar’s original sawtooth roof.

Welded connection plates from the new steel ziggurat to the hangar’s original steel roof trusses wasn’t a problem for steelwork contractor Midland Steel Structures. However, the roof trusses were extensively assessed during the design stage to make sure they were able to support and take the loads from the new structure below.

“Aircraft maintenance was carried out in the hangar and so the trusses originally supported overhead machinery. We were pretty sure the old steelwork was able to support the ziggurat, but we had to be certain,” adds Mr Daniels.

Located directly below the ziggurat a new raked 200-seat auditorium (lecture theatre) has been constructed. To achieve the required heightened headroom the hangers existing floor was excavated out to a depth of 1.5m.

Main contractor Haymills initially came on site in early 2007 and while construction work began on the new laboratory block, work also started on taking out the hangar’s innards as well as lowering the ground floor. Then, while it was building the predominantly concrete framed laboratory block, bases for the steelwork were also being installed for the ziggurat.

Spanning the lecture theatre and forming the underside of the first floor of ziggurat are a series of 14m long cellular beams. Cellular members were used where services needed to be kept within the structural void.

The ziggurat is connected to the rectangular laboratory block via three steel footbridges which stretch across the atrium. The bridges are cantilevered off of a lift shaft which has been formed with large meaty 219mm diameter columns, used primarily as architectural features.

The connecting atrium, which serves as an open light-filled space between the new four-storey block and the ziggurat is mostly formed with steel. A series of curved 193mm CHS fabricated sections span between the hangar’s original roof steelwork and the concrete walls of the laboratory block for the glazed roof.

Midland’s steelwork package did not begin and end with the highly innovative ziggurat and the attached atrium roof. The company also erected hanging steelwork onto which a rainscreen has been fixed which covers up an exposed steel framed plant area that is attached to one end of the laboratory block.

Interestingly the extension’s plant area has been stacked up alongside the new building, rather than located on the roof. All supply pipes and ducts then run horizontally into the labs. The services’ and plant area’s cladding, (hung from steelwork) is a perforated aluminium panelling which offers partial views of the contents as well as providing a stylish exterior to the building.