Projects and Features

Terminal takes wing at Farnborough

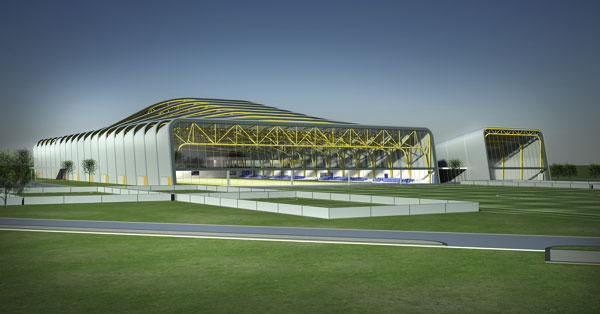

TAG Aviation’s new Farnborough terminal and operations building will look like a giant silver wing, as though the building itself has just touched down on the runway and taxied into position. Using steel was the only way to create it, David Fowler reports.

FACT FILE: TAG Terminal/Operations Building Farnborough

Project value: £10M

Client and construction manager: TAG Aviation (UK)

Architect: Reid Architecture

Structural engineer: Buro Happold

Steelwork contractor: Rowecord Engineering

Steel tonnage: 500 tonnes

At one end of the wing-like terminal structure you can see the complex steel frame, shrouded by scaffolding. At the other end, where the silver cladding glistens in the sunlight, the final shape is emerging and you can begin to see how the final building will look.

The terminal, a modern interpretation of the mid-20th century fashion for streamlining, complements the swooping shapes of the adjacent hangar and the new control tower opposite, both built in earlier phases of the development of Farnborough as a business airport.

TAG Aviation (UK), took out a lease to operate Farnborough as a business airport in 1998. The former MoD airfield served the aeronautical research facility on the site and the army establishment at nearby Aldershot, and continues to host the biennial air show.

Situated within easy reach of central London as well as Heathrow and Gatwick, though, it is in a prime location for business users.

The first priority for Swiss-based TAG, the leading business aviation service provider in Europe and the US, was to bring the 1930s facilities up to modern standards. The first phase comprised the new control tower, runway improvements and the hangar, was completed in 2002. A second hangar will follow in a later phase.

At the same time, TAG decided to move the focus of activity at the airport, including the terminal building, to the opposite corner of the site from the existing facilities, where they would be nearer the main road and further from adjacent houses.

The business and VIP passengers that Farnborough is seeking to attract will generally arrive and depart in small jets, often private, and unlike the experience at a large civilian airport, there will be only a minimal time lapse between check-in and take off. Because passengers will not spend much time in the terminal, or may even go direct from cars to their aircraft without entering the building at all, TAG considered it especially important that its new buildings should be strikingly modern. A design competition for the tower, hangars and terminal was won by Reid Architecture.

Phase one was managed by Bovis Lend Lease, but when construction of the terminal began last year, TAG decide to manage the project itself. Simon Horsley, who joined TAG as Project Manager from Bovis Lend Lease, says: “TAG looked at a number of procurement routes and decided to act as its own construction manager. We’re using the same architect and engineers as previously, and have established relationships with them and with key suppliers. We’ve identified good contractors such as Rowecord, who take ownership of the job and are good at co-ordinating work with following trades.”

Steel was the obvious choice for construction material, for reasons of speed, the shape of the building, which is curved in virtually every direction, and because tight tolerances are needed if the cladding is to have clean and smooth lines.

“If the building frame was out, as the cladding went up it would be really noticeable,” says TAG Construction Manager Don Graham.

There was close collaboration over the details between structural engineer Buro Happold and steelwork contractor Rowecord.

Paul Benwell, Rowecord Technical Director, says: “We produced a full 3D CAD model of the structure. In doing so a lot of geometric issues had to be resolved in consultation with Buro Happold and others. Because of the shape and type of cladding, there are a lot of sheeting rails close together. All the welded brackets for the sheeting rails were different.”

On the question of whether it would have been possible to build such a complex shape before the advent of 3D CAD, Benwell says: “We do more challenging geometry now because we can. In days gone by it would have been simplified.”

Tolerances were critical in the main ribs or hoops, which were induction-bent to radii as small as 2.7m by Angle Ring.

As well as arrival and departure facilities, the three-storey building includes two floors of offices, partly to be used by TAG’s administrative functions and partly to be let. There are also facilities for business meetings, convenient for executives who want to fly in purely for a meeting and then fly out again. An atrium, with a helical stairway, extends for the full height of the central portion of the building

Site erection of steelwork began in December last year and was completed in March 2005. The ground floor of the building is relatively straightforward, with two rows of exposed circular hollow section columns, filled with concrete for fire resistance. Curtain wall glazing of the whole of the ground floor will help to give the impression that the building is hanging in the air.

From the first floor the main frame consists of a series of 28 hoops at 9m centres, formed from 300mm deep UB section. These rake out sharply from the first floor slab, curve back over the building and finally rake back into the back at first floor level again. Between the curved sections at the front and back of the hoops is a long, central section supporting the roof decking, which, though straight, slopes from front to rear. The two ‘wings’ of the building are mirror images of each other, but otherwise each hoop is unique. To keep the atrium column-free, a fabricated box girder 22m long and 1.6m deep supports the central hoop. This beam is curved on plan, installed at an angle and precambered to cancel out deflection; a box girder was specified because, owing to its geometry, it has to resist both bending and torsion.

A lot of thought went into the construction sequence of the frame: “The trick is erecting it in the right sequence to take account of dead load deflections,’ says Mr Horsley.

The ends of the building are enclosed by vertical curtain wall glazing, from which a terrace juts out at first floor level. Two hoops set at an angle cantilever out beyond the main structure to form a canopy over the terrace.

Floors are composite using Holorib decking. At the front, there will be a reverse curved section at ground level around the main entrance from the airfield.

Fixing of the roof cladding followed quickly behind the erection of the frame. The wall cladding, however, is one of the trickiest parts of the job because of the curvature of the building and the need for a smooth, ripple-free finish. The outer surface is formed from 350mm square Mero aluminium shingles set at 45degrees — the shape of the building would not permit the use of anything in large sheets. In a somewhat labour-intensive operation the shingles, which were also used on the control tower, are folded and interlocked individually on site.

Conventional scaffolding is being used for access, because the outward rake of the building profile meant using any form of mechanised access was impractical. “Even the scaffold had to be faceted to fit properly,” says Mr Graham.

The results so far suggest attention to detail is paying off, with what appears to be a perfect curve appearing on the area clad so far. With the internal layers of the cladding system installed, the building was expected to be weathertight by the end of June, allowing work to start on fit-out and finish in time for the planned opening early in 2006.