Projects and Features

New role sought for pioneering tower block

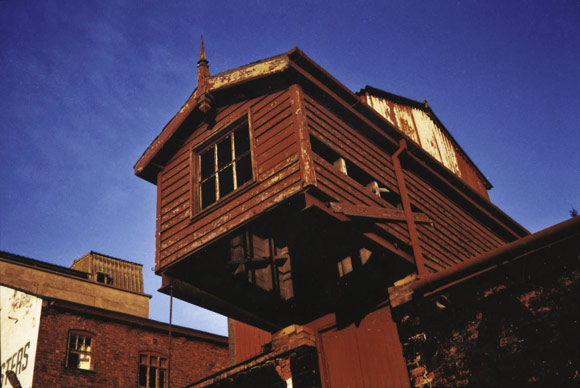

Ditherington Flax Mill in Shrewsbury has been acquired by English Heritage including the a later iron framed hoist structure from the 1850s Dye House

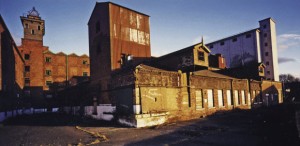

English Heritage has rescued the world’s first metal framed building, but the challenge now is to find a new use for it.

The historic forerunner of the multi-storey steel framed building has been saved for posterity after years of lying derelict.

After the failure of the latest development consortium to find a new use for Ditherington Flax Mill, in Shrewsbury, the building has been acquired by English Heritage.

When the mill was built in 1797 Shropshire was at the forefront of metal technology, Abraham Darby’s Iron Bridge having been built across the Severn just 20 years earlier.

English Heritage historic buildings inspector for the West Midlands Region John Yates says: “It wasn’t the first to use cast-iron beams or cast-iron columns, but it was the first use of beams and columns together in a three-dimensional metallic structure.”

The innovative structure employs cruciform cast columns, inverted Y-section beams and wrought iron ties

English Heritage has acquired the entire site, including two later iron framed structures and the hoist from the 1850s Dye House

What Mr Yates describes as a “brilliant piece of work” was the brainchild of Charles Bage who formed one-third of the partnership that built the mill, Benyon, Bage and Marshall. Marshall was the flax mill king of Leeds, and Benyon was a successful local businessman who put up funding. Bage, a local surveyor, was the brains behind the design.

The driver for adopting a novel method of construction was fire resistance, at a time when this type of building normally had a high timber content.

The five-storey Ditherington Flax Mill uses cruciform cast-iron columns a single storey high. They widen slightly at mid-height but are very slender by today’s standards at around 5in at their widest point. They are arranged in three rows, dividing the building into four bays of around 10ft wide.

Cast-iron beams span between the columns. They have an inverted Y-section with the space between the arms of the Y filled in; from the sloping sides of the beam a shallow jack-arched brick floor is built. Wrought-iron ties running at right angles to the beams resist the thrust from the arches.

The beams are bolted together rigidly off the line of the columns, and hence act as continuous rather than simply supported, producing a zone above the supports in which they are in tension. Cast-iron is, of course, not strong in tension: “There are a few fractures above columns due to overloading,” says Mr Yates.

The beam/column connection employs a male/female joint which slots together and otherwise depends only on gravity to hold it together, with a pad of lead to account for casting irregularities.

The columns are spaced at around 10ft centres in each direction and divide the building into four bays. The internal structure is not expressed at all on the outside of the building, which has loadbearing brick walls.

Little is known of the structure’s creator, Bage. He is thought to have moved “in the same circles as Telford”, though there is nothing to link him directly to contemporaries such as Abraham Darby, and he is not known for any other works.

His system of building was influential, though, and was widely copied especially in North West England. It was also adopted extensively throughout the next century for building railway underpasses.

”The idea you could do the whole thing in metal was further developed by others as wrought iron became more widely available in bigger sections,” adds Mr Yates.

After serving for 100 years as a textile mill, and a further 90 as maltings, providing raw materials for the brewing industry, the mill has been disused since 1987 and had fallen into a poor state of repair. Successive developers have tried and failed to get schemes to turn it into offices, flats, retail units or a mixture off the ground.

“The mill was built very elegantly and economically compared with later structures, and the loadings it can take are less than might be expected,” says Mr Yates.

Priorities now, says Mr Yates, are “a further round of emergency repairs, making it secure and accessible for people to see inside while its future use is established.” There will be a new phase of a feasibility study to analyse options for a viaible use for the building.

“It’s a particularly challenging building because of its lightweight construction,” Mr Yates concludes. “It’s a marvellous piece of construction but they were flying a bit close to the sun.”