Projects and Features

Children help create hospital with ‘wow’ factor

The new Evelina Children’s Hospital in London sets new standards for design and patient care, as Margo Cole reports.

FACT FILE: The Evelina Children’s Hospital

Developer: Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Construction cost: £41.8m

Architect: Hopkins Architects

Structural engineer: Buro Happold

Main contractor: Gleeson

Steelwork contractor: S H Structures

During the Victorian era hospitals, like most public buildings, were designed to inspire, impress and instill wonder and awe. We may argue now about the merits of their design in terms of modern clinical practices, but it is extremely rare to find a new hospital building that incorporates a genuine “wow” factor, as they did.

How refreshing it is, then, to see the completion of the Evelina Children’s Hospital, a specialist unit of St Thomas’ Hospital on London’s South Bank. The building manages to be child-orientated while having extraordinary architectural merit and also enabling the highest possible standards of clinical practice to be achieved.

The Evelina’s design is the result of a RIBA-hosted architectural competition instigated by Guy’s and St Thomas’s Charity in 1999 — the first ever such competition for a major healthcare facility. The charity, which dates back to the 16th century, has provided £50M of the £60M cost of the new hospital.

Having won the competition, a design team of Hopkins Architects and structural engineer Buro Happold entered into discussions with the client — Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust — its patients, staff and the local community to provide a hospital that, in the words of children being cared for at Evelina, “doesn’t feel like a hospital”.

Children have played a huge part in the design ethos, as well as in the details. Most children’s wards in major hospitals are really adult facilities with the addition of a few toys and posters. Evelina is a genuine children’s hospital, and children have been consulted on everything from the fundamental design to the food in the canteen.

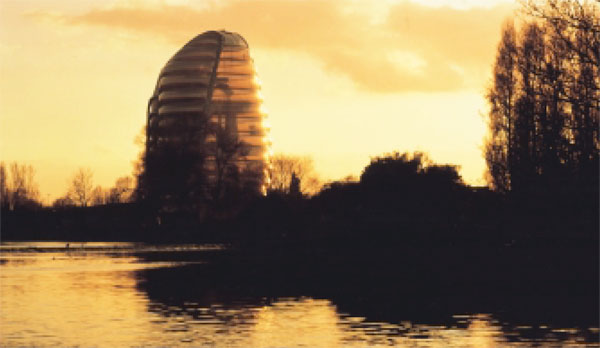

One of their first requests was that the building should be airy and spacious and make them feel like they are outside. “That,” says Buro Happold’s project engineer Matthew Grant, “is how the conservatory came about.”

The conservatory is the hub of the new hospital, a four-storey atrium running the entire length of the building and covered by a fully glazed, curved, steel-framed roof. It is a magnificent space that, by virtue of starting at the third floor, succeeds in its aim of bringing the outside — in the form of sky and trees from the adjacent park — right into the building. There is also access to a roof garden for patients well enough to venture outside.

The hospital’s design consists of a simple L shaped section with the lowest three floors housing the most intensely serviced functions such as operating theatres, MRI scanner and outpatients. Huge light wells punched through from the third floor conservatory level bringing light into these deeper plan spaces. To the north three ward levels and an office space are stacked on top of each other, benefiting from the stunning views through the conservatory that sweeps from the southern edge up to the roof level.

The structure of the giant arched roof, which spans 20m in height and 18m in width, is a steel gridshell made from 273mm diameter circular hollow steel sections. Its curved design generates large horizontal forces, so the entire structure is tied back into the concrete frame of the main blocks both at third floor and roof level.

“The arched roof is trying to push outwards, so it is tied back into the concrete frame using large tie members,” explains Mr Grant. But the connections are pinned joints, so the only loads are the horizontal and vertical thrust.

All the loads that are transferred into the concrete frame go back to four stability cores.

On most of the conservatory roof the glazing follows the curve. However, the lower portion on the south side has vertical glazing, allowing the curve of the structure to continue externally, creating a walkway. At the intersection of the vertical glazing and the curved roof there is a hinge detail that allows the vertical portion of the glazing to move independently of the rest of the roof. “Without this articulating joint the load would be going through the glazing support,” explains Mr Grant.

At each of the conservatory’s side elevations a row of vertical aerofoil-shaped trusses takes the wind loading and provides horizontal restraint for the glazed facades.

“The whole design concept of this roof was to design something that could be built 20m up in the air and with limited crane access,” says Mr Grant.

Steel fabricator SH Structures was called in during the process to advise on buildability. “We spent a lot of time talking to the industry about how we were going to build this,” says Mr Grant. “It acted as a reality check so the design team didn’t go off on one tack and the industry on another. The design of the roof had to take into account building tolerances because it was all going to be built on site.”

The eventual construction method agreed between the design team, SH Structures and the main contractor Gleeson, was to build the gridshell as a series of vertical trusses. Steel sections arrived with two pieces linked — like a wishbone — by a cruciform joint. Another two sections were then fitted to the joint on site and welded into position, with this process continuing to the full height of the building before starting on the next truss along.

The gridshell was not stable until the whole frame was in place, so the entire floor area was scaffolded out during construction to support the steelwork in the temporary condition. The scaffolding then stayed in place while the glazing was fixed.

SH Structures manufactured the steel to cope with anticipated deflections, and the glazing was manufactured to fit the frame in its deflected state.

A key buildability issue was managing the interface between the steel roof and the concrete frame. “We knew we would have to take all the building tolerances out with the steel,” explains Mr Grant. “With steel construction you can achieve very tight tolerances but with concrete they are a lot wider, so we had to accommodate this within the connections.”

Each of the main pinned connections at the top of the roof is fixed to a steel plate that is itself attached to another steel plate cast into the concrete. This method enabled both horizontal and vertical alignment to be adjusted to take account of the finished concrete levels.

The concrete frame itself is of flat slab construction, so large steel beams were cast into the slabs to accommodate the thrust from the gridshell structure.

Although predominantly concrete-framed, the lower section of the hospital building does incorporate a major piece of steel construction in the form of a transfer truss at lower ground floor level. The structure is needed to create an accessway large enough to allow fire appliances to get beneath and around the building. This could only be achieved by removing two columns from the 9m grid and spanning the gap with a tubular steel truss, which supports the load from eight storeys of hospital above.

“The truss is one full storey height deep, and it is working very hard,” says Mr Grant. “There are 250 tonne point loads coming down to each of the third points, which is higher load than you get on most bridges.”

The truss weighs in the order of 20 tonnes, and Gleeson had to bring in the UK’s largest portable crane to lift it into place. Large steel columns encased in the walls either side of the opening, and which are tied back into the reinforced concrete core wall, provide support for the truss.

Although the building has been finished since March, fitting out took a further six months. This not only gave time for specialist equipment — such as the MRI scanner — to be installed, but also for large amounts of specially-commissioned artwork to be fixed into place. The first children themselves were admitted the Evelina Hospital in mid-October.

The Hospital

The Evelina Children’s Hospital can accommodate 140 in-patients, 20 of them in intensive care beds. The beds are in clusters of between four and eight, and each is accompanied by a drop-down bed for a parent or relative.

Each floor of the hospital has a theme based on the natural world, with signage and names designed to match the themes. They are — from the ground up — Ocean, Arctic, Forest, Beach, Savannah, Mountain and Sky. In-patient beds are on levels three to five (Beach, Savannah and Mountain), with each area named after an animal that could be found in that part of the natural world (Camel, Crab and so on). Artwork reinforces these themes.

The Conservatory (on Beach level) houses a school, café, performance areas and Radio Lollipop, the hospital radio station. It is expected that patients well enough to get out of bed will meet their visitors in this area, and there will also be performances and opportunities to meet celebrity visitors. Children unable to leave their wards can look down on the Beach, as all in-patient bed areas face the Conservatory.

The Evelina has been designed to incorporate almost all the specialist services that might be needed, so it is only on rare occasions that children will have to go to the adult hospital next door.

Most of the funding for the hospital has come from Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, which supports hospitals in Lambeth and Southwark. The Charity also administers the appeal that is raising money to supply specialist equipment to the hospital. One per cent of all the money donated by the Charity has been spent on art.

For more information on the appeal go to www.evelinaappeal.org