Projects and Features

Shopping with steel

Sustainability, cutting edge design and the reuse of materials are all key factors in the redevelopment of a steel-framed former department store in London’s West End.

FACT FILE

Elephant, 318 Oxford Street, London

Main client: Publica Properties

Architect: Studio PDP

Main contractor: McLaren Construction

Structural engineer: Civic Engineers

Steelwork contractor: Severfield

Steel tonnage: 1,200t

Completed in 1937, the D.H Evans department store at 318 Oxford Street was for many years one of the capital’s most well-known emporiums.

Later becoming part of the House of Fraser, the art deco store was once on a prestigious shopping list of London department stores alongside Harrods, Selfridges, and some that are no longer trading, such as Whiteleys and Gamages.

Having weathered the changing climate on the high street during the early part of this century, the store closed down during the Covid pandemic in January 2021.

Plans were quickly drawn up for a redevelopment, as the store’s demise had left a vacant, and large historic steel-framed building on London’s busiest retail street.

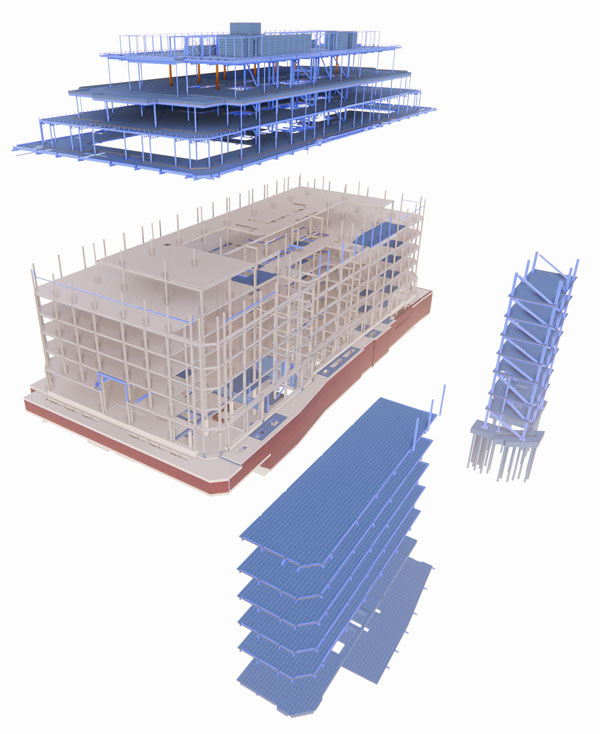

Demolishing the structure and starting again with a completely new building was not a sustainable option. So, in early 2024, main contractor McLaren Construction began a £132 million refurbishment and extension programme, repurposing the store into a 34,000m² mixed-use scheme.

The new building, rechristened Elephant, will have retail units, restaurants, and a gym on the lower ground, ground and first floors. Above this, there will be modern office spaces on levels two to seven, and a penthouse restaurant on the uppermost eighth floor.

The construction programme consists of two phases, with the initial work involving a traditional cut-and-carve approach to the lower floors. The work includes retaining a large proportion of the façade and structure, which significantly reduces the new building’s whole-life embodied carbon.

Within the retained structure, new openings for lifts and stairs were created, two double-height entrances for the offices were formed, a new steel-framed core was installed and the upper two floors were demolished in readiness for the next stage.

“In the second phase, we added three new floors above the existing structure to accommodate more office spaces, the restaurant, as well as a rooftop Building Maintenance Unit (BMU),” says McLaren Project Director Simon LeFevre.

The project team estimates that the new reconfigured building generates almost the same loadings as the old structure. However, to accommodate the new floors, strengthening works to the existing structure had to be undertaken, along with the installation of some new foundations.

Forming an architectural feature, the new and old steelwork in the scheme will be exposed in the completed building. Previously, the original 1930s-made steel columns and beams were hidden behind encasements or ceilings, but rivets and all, they will now be on show.

Severfield was awarded the steel package and estimates that it erected approximately 600t for each phase. The largest steel element in the first phase was the installation of a new core, which required approximately 260t of steelwork, including columns weighing up to 4t each.

“The building didn’t have any structural cores, but relied on brick masonry walls built between the steel frame for stability. Those walls have been taken out to create open plan spaces and a new structural core is designed to take all the lateral loads of the building,” explains Civic Engineers’ Associate Director Simon Bennett.

Where to position the new core was a challenge, as the design team did not want to put it in the middle of the building, since it would have eaten up a lot of valuable floor space and necessitated additional demolition work.

The solution was to use a large escalator void, which was originally going to be in-filled. Using the site’s tower crane, individual steel elements were carefully lifted into the void to form the braced steel core, which measures 17m × 8m on plan.

Sustainability has been a key focus at 318 Oxford Street, and the project team implemented several strategies to reduce waste and repurpose materials.

As part of the cut-and-carve and demolition of the original upper floors, 10 columns from the fifth floor were removed and reused as part of the steel frame that forms the new upper levels.

A further quantity of beams (approximately weighing 80t) were surplus to requirements; consequently they were transported across London and reused within another project close to Tower Bridge (see NSC February 2024).

For continuity and ease of construction, the new steelwork follows the same structural grid as the original building. However, the perimeter and internal columns were set out on different grids, meaning the design for the new upper floors had to mimic this unique pattern.

Alongside the reused columns, new CHS sections have been connected to the original steelwork to form the internal frame for the new floors.

The existing floors of the building were constructed using precast planks, but the new steelwork supports metal decking and a concrete topping for a composite solution.

Terraces on the sixth, seventh, and eighth floors have been incorporated into the design, creating outdoor spaces for the future tenants.

Sat on the roof of the eighth floor, one of the final steel elements to be erected was a 90m-long frame that supports a track and a BMU.

With a 32m-long arm, the BMU is a large piece of kit that will be able to move up and down its track to reach every part of the building’s four elevations.

Elephant, 318 Oxford Street is due to complete in Autumn 2026.

Reusing historic steelwork

The newly completed 318 Oxford Street is an excellent example of the construction industry’s shift towards a more sustainable approach to redevelopment. A key feature of the project is the retention of the building’s original 1930s steel frame. Max Cooper of the SCI offers readers guidance on the engineering challenges involved in working with historic steelwork, which pose different problems from those encountered in standard design practice.

When approaching the appraisal of an existing building steel frame, engineers need a framework to assess its adequacy safely and efficiently. Readers are directed to the guidance in SCI Publication P138, Appraisal of Existing Iron and Steel Structures. It provides a detailed methodology for assessing structures built with early steel, as well as wrought and cast iron. The guidance helps engineers understand the differences in materials, fabrication methods, and design philosophies of the past.

A core principle of P138 is that appraisal of an existing structure where the proposed loading is unchanged or similar to the original design is different from new design. If the structure shows no signs of distress under its existing loads, it may be sufficient to prove its adequacy by simply evaluating the structure to the standards of its time.

However, when loads change significantly, as with the addition of three new floors at the 318 Oxford Street, a more detailed assessment is required. P138 advises using modern limit-state principles but with modified partial safety factors. At the time of publication, BS 5950 was the most modern code, but the principles may be applied equally to Eurocode 3. For historic steelwork, a material factor (γm) of 1.2 is suggested, which is taken from the highway structures standard BD 21. P138 provides typical permissible stresses and useful information for identifying materials and assessing historic connections along with advice for the repair, strengthening or even replacement of existing sections. Guidance can also be found on how to make connections to existing steel, and methods to determine the weldability of historic steelwork.

The reuse of existing building structures will become increasingly common as engineers look for ways to reduce the embodied carbon associated with their designs. The information given in SCI P138 is an invaluable resource for engineers looking to retain steel structures and give them a new lease of life. Not only does it help achieve sustainability goals, but it also plays a part in preserving the interesting heritage of the steel construction in the UK.

- BMU

- Civic Engineers

- exposed steel frame

- extension

- London

- McLaren Construction

- Metal decking

- mixed use

- new core

- Office

- Oxford Street

- P138

- P138 Appraisal of Existing Iron and Steel Structures

- precast planks

- refurbishment

- restaurant

- retail

- reuse of steel

- reuse of steel frame

- Severfield

- strengthening

- Sustainability

- tower crane