Profile

Riding high

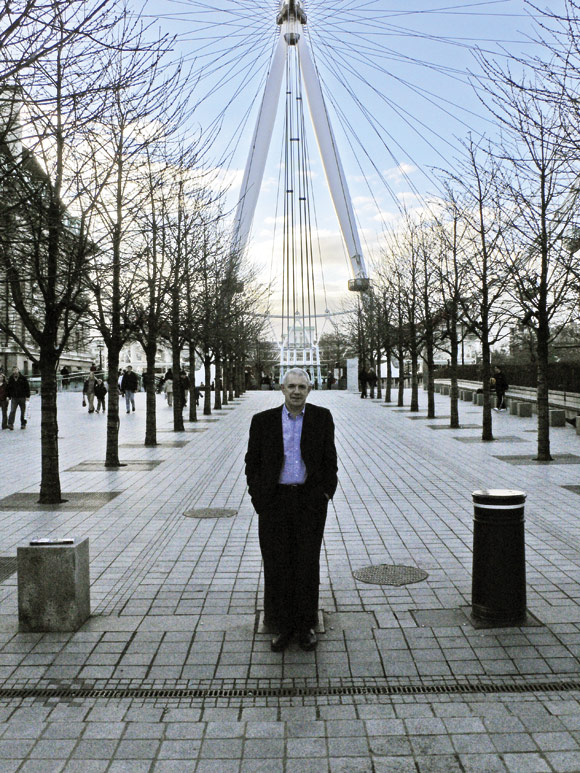

Having the London Eye and Pepsi-Max roller coaster on his CV helped John Roberts obtain IStructE’s latest Gold Medal. Ty Byrd reports.

Award of the Institution of Structural Engineer’s Gold Medal is never for nothing: the medal is high prestige and the latest recipient – Dr John Roberts – got it for helping raise public awareness of big structural projects. This he has done not least as a television pundit on engineering matters given credibility with the public by his involvement in two high profile steel structures.

Both of these are the biggest of their kind: the 135m London Eye observation wheel and the Pepsi-Max Big One, Blackpool Pleasure Beach’s world beating roller coaster. Roberts and his former firm Allott & Lomax – now Jacobs Babtie – enjoy a kind of cult status as Britain’s leading experts on passenger carrying rides. “We do other things as well,” he says, “but it is the big rides that get the attention.”

Roberts is, in fact, one of Britain’s leading structural engineers, having been President of IStructE in 1999-2000. He served as director responsible for structural engineering at Allott & Lomax from 1985; and since 2000 he has been head of Jacob Babtie’s building structures division. His name is attached to many major structural steelwork projects. All that said, he has a soft spot for theme parks in general and rides engineering in particular, carried out by his specialist team in Manchester.

Alton Towers, Chessington World of Adventures, Tusenfryd Park in Oslo and the London Dungeon have all got structures in whose existence the consultant has played or continues to play a part. Robert’s firm carried out the engineering design of the Pepsi Max and was appointed consulting engineer on the London Eye to verify the adequacy of the structure and oversee its safety, a responsibility it continues to exercise today. There are other rides at home and overseas (either operational or planned) with which the firm is involved. The engineering is highly specialised and the fact there are not many specialists is a matter of some delight.

“We had to learn it all from scratch,” Roberts says, “having been introduced to the discipline by chance.” One of his engineering colleagues, a water and drainage man, met a director of Blackpool Pleasure Beach while on holiday abroad. He learned the leisure company was looking for an independent engineer to carry out safety checks on its rides. John Roberts subsequently met the Pleasure Beach owner and put forward a proposal, freely admitting his firm had no specific knowlege of roller coasters, but claiming lots of knowledge of structural engineering per se. “We were appointed consultant, given a crash course in how rides work and told to get on with it. That was in 1985 and we’ve worked for them ever since. It’s been great.”

Rides are so interesting, especially in their maintenance he says. “They are not static buildings but operating machines withstanding enormous dynamic forces. Maintaining them, you find out how structures perform, you really find out about fatigue.” The leisure and theme park world is similarly fascinating, involving strong and colourful clients. One such was John Broom who owned Alton Towers in the 1980s. “He rang to say he had bought the mono rail trains from Expo 86 in Vancouver and that they were on their way by container. This was February 1988. ‘I want the monorail up and running in 16 weeks,’ he said. I said: ‘In that case, we’d better get our fingers out’.”

The track was 3.5km of steel box girder in a loop, supported by steel columns on 88 foun-dations. There were two stations. The lot was to be competitively tendered. “And we did it on schedule with Fairfield Mabey performing well as the fabricator.” One item not carried out in the time was temperature analysis. “We warned that this would have to be done later, and subsequently retrofitted additional foundation tie down bolts to counter the effects of winter cold.” Mr Broom did not moan about the late bill for this, it seems. He probably believed that, overall, he had a bargain. Captain Kirk of the Starship Enterprise opened the ride to much publicity, and was paid more for his efforts than the consulting engineer was for its. “I learned from this,” Roberts says.

One thing that pleases him about the development of passenger carrying rides as a specialism is it has given continuing relevance to some abstruse research he conducted 35 years ago for his PhD. He looked into impact overload of steel structures which, “against all the odds”, has proved very useful in the years that followed. His three year PhD was carried out at Sheffield University, from which he had graduated with a first class honours degree in civil engineering. “I think I was a late developer, academically,” he says now. “Certainly, that’s what my parents used to say.”

Perhaps they just wanted to keep his feet on the ground. John Roberts was a product of England’s first purpose built comprehensive school, in the Bristol constituency of Tony Benn. He had passed the 11+ but his mother did not favour the grammar school. He obtained three good A levels and sat the Oxford Entrance Exam before finding out that his chosen subject was not an option at Oxford.

“As a sixth former, I spent two summers labouring on construction sites, the second one working all God’s hours soil testing for the M5. I earned enough money to buy a Mini Cooper S and thought, crikey, if I can earn this much as a labourer, how much more will I earn as a civil engineer?” He plumped for Sheffield, a good steel town, in search of a good education and real wealth. “I actually won the British Iron & Steel prize when I graduated which involved lots of dosh. Well, £30 seemed like lots in the late 1960s.” He married his girl friend Angie in 1969, she just having finished teacher training college and willing to be sole wage earner for the next three years. “One of us had to bring in money during my PhD,” he says.

John Roberts worked for contractor Sir Alfred McAlpine between 1972 and 1974 (“I didn’t tell them about my PhD in case they wouldn’t employ me”), then consultant Bertram Done & Partners for seven years before joining Allott & Lomax in 1981; spending all his working life based in Manchester. He has been project director on the likes of the SAS Radisson Hotel at Manchester Airport, Victoria Buildings on Salford Quays and the Battersea Power Station redevelopment – as well as lots of theme park schemes. He holds the chair of visiting Professor in Principles of Engineering Design at the University of Manchester; and sits on the Councils of both the Steel Construction Institute and the British Constructional Steelwork Association.

Enthusiasm bubbles out of him, seemingly about everything he does. Being part of the Jacobs family pleases him greatly – “now I can pretend I’m an American” – because this means it is easier to work in the States and Jacobs Babtie can draw on immense profes-sional resources in the US. His enthusiasm for Europe, in particular Eurocodes, is less easy to discern. Perhaps the fact that he has proposed to colleagues a moratorium with regard to Eurocodes activity at the moment gives a clue to his thinking. “It’s much more fun designing rides,” he says.