Technical

Rare problem can be easily avoided

BCSA and the Galvanizers Association have published a guide on minimising the risk of a rare phenomenon, liquid metal assisted cracking (LMAC). BCSA’s Director of Engineering David Moore outlines the practical steps to take.

LMAC is an uncommon form of cracking and because of this it will be new to many engineers. A new guide from the BCSA and the Galvanizers Association contains practical advice to clients, designers, steelwork contractors and galvanizers to assist in the development of designs and details with low susceptibility to LMAC, and gives an appreciation of the relative importance of the factors adding to that risk from practical experience.

The galvanizing of structural steelwork is a long established and cost-effective way of providing economic and long-lasting protection against corrosion, with low maintenance requirements and good damage resistance. Indeed, the UK galvanizing industry galvanizes some 800,000 tonnes of steel annually, an increase of a third over the past decade. Furthermore, larger zinc baths have been introduced in response to the construction industry’s needs to hot dip galvanize longer and larger components. The UK boasts the longest bath in Europe (at 21m) and there are another twelve baths in the UK and Ireland in excess of 10m long. Figure 1 shows a typical steel section being galvanized.

In recent years the phenomenon known as Liquid Metal Assisted Cracking (LMAC) has been recognised as a form of cracking that may under some circumstances occur during the galvanizing of structural steelwork. Although this form of cracking is uncommon, if it is not detected and repaired it can compromise the performance of the structure.

Certain solid metals when in contact with other liquid materials can give rise to a reaction, which will affect the parent solid metal. Susceptibility to these conditions occurs only in specific metals and environments, and is known under the generic title of liquid metal embrittlement. One of the situations where this can occur is when structural steel is stressed and in contact with liquid zinc as happens during the galvanizing process. This form of cracking is characterised by a crack through the entire cross-section (an example of LMAC is shown in figure 2).

Generally, such cracks are initiated at fabrication details such as welds, gas-cut edges, holes etc.

The occurrence of LMAC is sufficiently uncommon that no coordinated programme of research or information gathering has been put in place in the UK. However, some research is ongoing at present in the UK. While evidence from Germany, Japan, the USA and other countries has highlighted the occurrence of LMAC, an authoritative understanding of the circumstances that may trigger the cracking remains elusive.

It is, however, recognised that a range of factors can and do influence the onset of LMAC, and that the inter-relationship of these factors is also of crucial importance to any understanding of the phenomenon. The relative weighting of these factors has yet to be defined but what is clear is that all the partners in the supply chain for galvanized articles have some part to play in influencing the level of risk associated with LMAC.

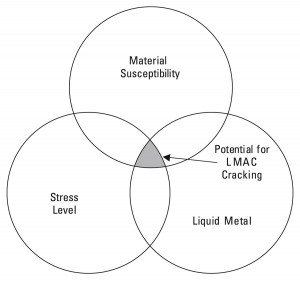

It is generally accepted that there are three main prerequisites for LMAC to occur. These are:

- stress level

- material susceptibility

- liquid metal

It is also self evident that all three may, on rare occasions, be present at a required ‘critical combination’ when fabricated structural steelwork is hot dip galvanized thereby exposing the article to risk of LMAC occurring.

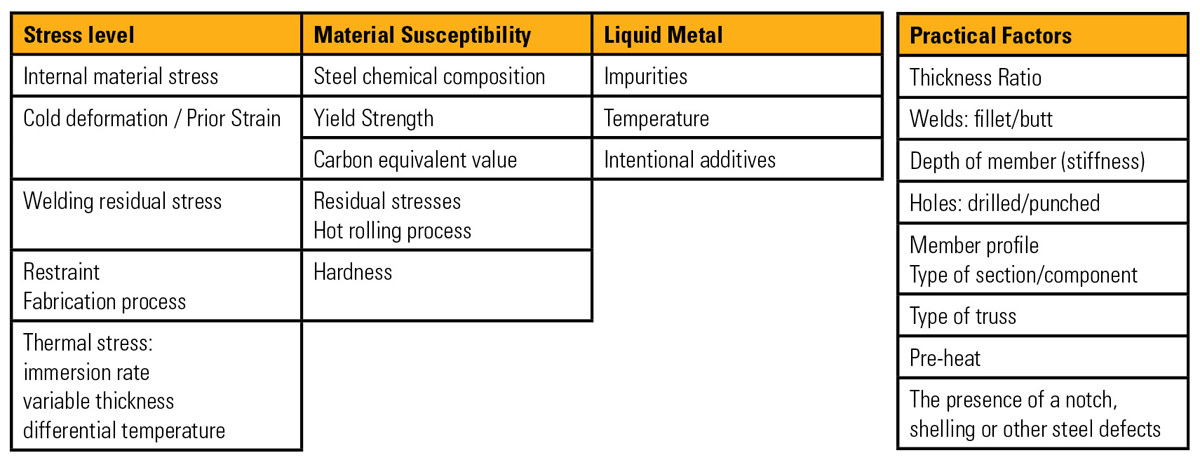

It is perhaps more important to recognise the individual and independent factors within the three prerequisites given above. Table 1 shows the breakdown of these three prerequisites into their constituent factors. The lack of knowledge surrounding LMAC has to do with the inter-relationship of these individual factors, and their relative ‘weighting’ in increasing the risk of LMAC. So, although the basis of the mechanism is recognised, the details of how material susceptibility and liquid metal (severity) factors may vary and affect the ‘risk’ are not known.

To help minimise the risk of LMAC occurring the new publication gives practical guidance on each of the following topics to identify circumstances where any increased risk of LMAC can be ameliorated.

- Design and detailing,

- Type and quality of steel

- Quality of fabrication

- The galvanizing process

A post-galvanized inspection regime is suggested as a pragmatic approach to further reducing the potential consequences of LMAC on the structure. It is recommended that the Engineer should specify 100% visual inspection after galvanizing for all structural steelwork that is to be utilised in building construction. This should be written into the Project Specification so that all parties are fully aware of the requirement. In the event that some LMAC defects are found, then it is important that the Engineer should consider the potential implications of such cracking and modify the Project Specification as required to include further non-destructive testing in critical areas. The Engineer should also agree with the Steelwork Contractor and then instruct under the contract appropriate repairs to be completed on any defects that have been found.

The advice given in the new publication is applicable, primarily, to galvanized structural steelwork for building construction in the UK. It is based on steel grades S275 and S355, although the principles, if used with care, can be applied to the management of higher strength grades of steel. The methodology may also be modified for bridge structures or series-production of steel ‘components’. However, if the structure is to be subjected to fatigue loading the consequences of structural defects are far more critical and the Engineer must consider the inspection regime in the light of these consequences.

The occurrence of LMAC depends upon a range of factors coming together at the same time. These factors derive from the design and detailing of the component, the condition and quality of the steel, detailing and fabrication and the galvanizing process. The weighting of the individual contributions from each of these activities is not known and no single factor, at this time, can be identified as the major contribution to LMAC. By following the guidance given in this document and by committing a modest amount of attention to detail at each stage of the construction process the chances of LMAC occurring can be substantially reduced.

Galvanizing structural steelwork – An approach to the management of liquid metal assisted cracking

Price: £15(UK), £18(EU/overseas), £21(outside EU)

Member £11.25(plus P&P)

Author: BCSA and GA

ISBN: 0850730481

A4: paperback

Copies of the publication can be obtained from:

The British Constructional Steelwork Association Ltd

(Publications Dept)

4, Whitehall Court

Westminster

London

SW1A 2ES

Tel: 020 7839 8566

Fax: 020 7976 1634

Email: don.thornicroft@steelconstruction.org

Alternatively it can be downloaded from BCSA’s web site – www.steelconstruction.org