50 & 20 Years Ago

One-offs

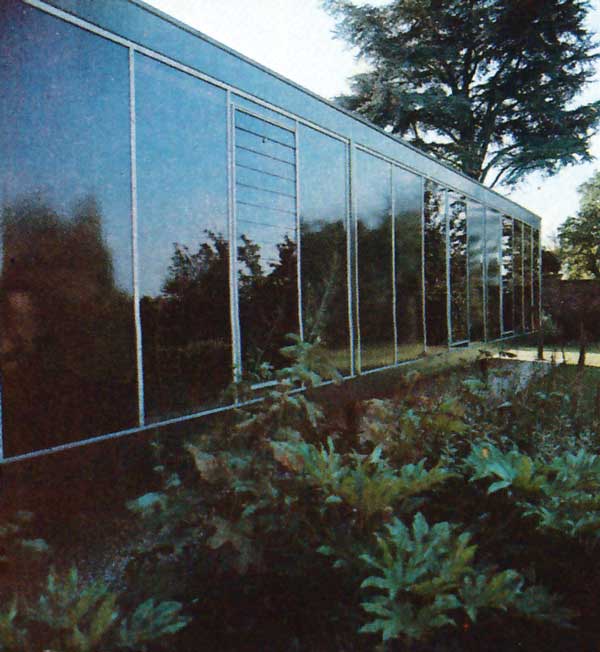

Architects: Katz Vaughan & Partners.

There will always be houses designed exclusively for their occupiers – one-off design in fact. Among the architects who have handled this work is Michael Manser who writes about his approach in this article. He has been particularly successful with steel components.

There is a quotation, attributed to Emile Coignier, that “Enduring architecture is created when the imperatives of a structural technique are mastered”, and it is true. There is no special magic in any particular building material. Architecture can be made from pressed seaweed and matches if necessary. It is the skill and sensitivity of the designer that creates a successful building. There is no safety in using stone, brick or timber. More terrible buildings are made of mellow brick than any other material, nothing is more forbidding and gloomy than mishandled stone, and timber has been the cause of many shanty towns. Although no building type is more vulnerable to architectural failure than a house, it is in the housing field that architectural innovation usually occurs and to date there have been some spectacularly successful houses built in steel – particularly in the ‘one-off luxury end of the market.

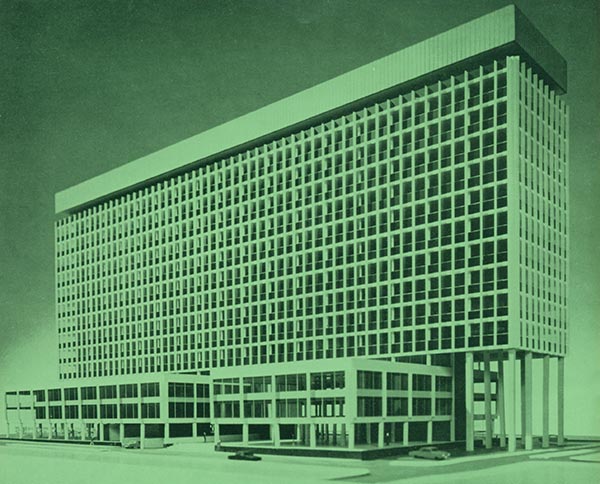

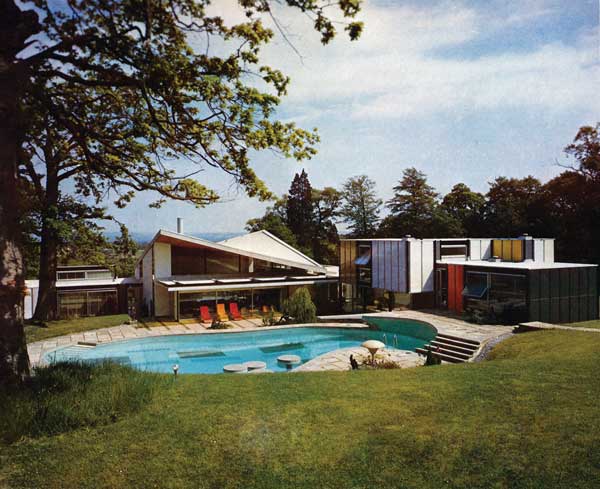

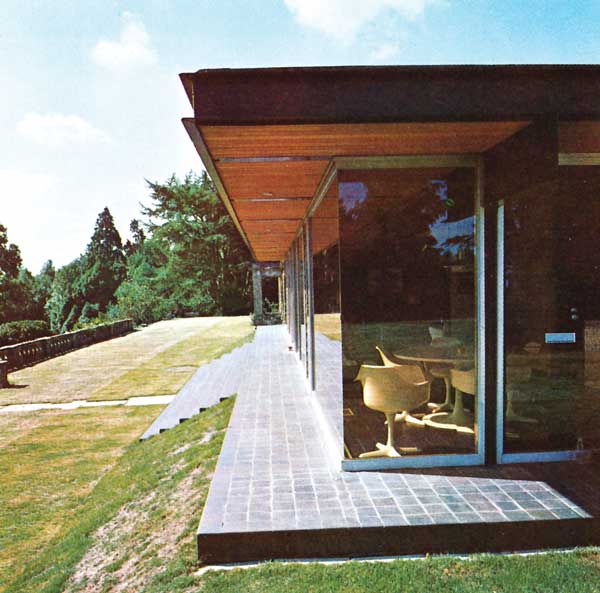

The reason is probably that steel is a material of great intrinsic character and it imparts a rigorous discipline on the designer. It is one thing to use bits of steel to hold up awkwardly large spans in a conventional structure. It is quite another matter to accept the rigid grid of a steel frame and form within it a comfortable home. To do this is to accept a degree of formality, to design in straight lines – the ‘regular lines’ of Palladian architecture – to accept regular spacings of columns and be prepared to choose all other materials for their ability to fit within the frame of steel. Used well, a steel frame can give a house the simple formal excellence of the best of Georgian domestic architecture – but opened up and out by large spans and glass walls to achieve a scale and drama technically far beyond eighteenth-century capability.

Architect: Michael Manser Associates.

Apart from the aesthetic possibilities of steel there are practical advantages, largely to do with speed and labour saving, which as building costs rise become more and more important.

The steel frame does not require labour intensive strip foundations. The load of the building can be gathered up and taken into the ground on perhaps six or eight ‘legs’ and these only need concrete ground pads. If the subsoil is poor and requires piles then the saving is greater. There needs to be no over-site concrete and screed and therefore internal services and plumbing can be attached to the underside of the steel frame and remain accessible without excavation for later maintenance.

If the land has a slope – stepped foundations and walls are avoided because the length of each ‘leg’ can be adjusted so that the building floats just above the highest part of the land. Once the frame is up, which takes a few days, the roof can be placed and the enclosing wall cladding fixed. From then on the building becomes its own workshop and all bad weather working is avoided. Earlier on the use of steel was inhibited by its cost – which is now more than offset by labour and weather savings and also by its need for fire protection which again is now overcome by patent dry column claddings of asbestos and pressed steel and the use of intumescent paints. These are paints which foam up to one or two inches thickness when exposed to heat and protect the steel.

Another advantage of steel as a building material is that it is comparatively light to handle and can be erected dry. It is also easy to dismantle and alter and re-erect – virtually impossible in a conventional masonry construction. In the latter half of the twentieth century when the rate of change has accelerated far beyond that of any previous generation it seems inconceivable that we are now building in the prefabricated concrete systems the heaviest and most enduring mass housing that has ever been known. It seems extraordinary that anyone thinks of 8in of solid concrete or brick is still necessary to protect a family from the weather when the same family fly to their summer holiday at 600 miles per hour 30,000 feet above the ground in an aeroplane offering only about 2in of assorted aluminium and insulating quilt protection between them and certain and instant death.

Steel is an ideal construction material of great permanence, and easy to maintain. It is ironic that many families who lived in great comfort in post-war steel prefabricated houses were transferred to traditional homes as soon as they could be built. There was really nothing wrong with the prefabs except that they were conceived on minimal accommodation standards. They were designed to last ten years, but twenty-five years later they were superseded, not technically, but because their scale of accommodation was inadequate. If a little more thought had been put into their initial design to make them larger and less boxlike in appearance, if their creation had not been inhibited by irrelevant considerations of permanence or impermanence and if they had been laid out in less barrack-like estates – they could have been made part of the permanent housing stock and the double effort of re-housing avoided. After all, what is permanent. The prefabricated home with a planned life of ten years lasted twenty-five and was clearly good enough for thirty or thirty-five years. Obviously only a marginal upgrading of quality would have given them a minimum effective life of sixty years, which is all that is required. From this point on, it is a question of quality of maintenance that extends the useful life of any structure.

Architect: M. Manser & Partners.

But the interesting thing about the prefabricated houses was that they were delivered half at a time on two lorries and each half was factory completed. When replacement time came, some were even dismantled the same way and re-erected. They were designed nearly thirty years ago and although there are some similarly constructed timber houses now on the market there is nothing available in steel – which has a much greater potential.

Even the old corrosion bogey of steel has been over stated. All building materials are vulnerable to deterioration by the weather and the longevity of each is dependent upon the way each is detailed to diminish the effects of weathering.

Steel is no exception. It is possible to detail bare steel so that the run off is quick and the rate of corrosion extremely slow. Comparatively recently, weathering steels have been introduced, the most well known being Cor-Ten. These are steels whose specification is such that a protective patina of rust forms over the steel which then corrodes at an enormously diminished rate. Aesthetically they have great appeal as the final appearance settles at a nutmeg brown colour. Galvanizing is another way of protecting construction steel but steelwork treated with an ordinary paint finish can be a minimum maintenance liability. Provided the details are such that rainwater cannot lie in pockets and steel surfaces are recessed to be protected from direct weathering, by projecting roofs, etc.

Despite the practical and economic justification, as far as I am concerned it is the aesthetic qualities of steel that are so interesting. Only steel housing seems to properly reflect the precision working which is the main achievement of our generation.

House components should be made in a factory and quickly assembled on site and for this they need to be lightweight and erected dry. This aim poses problems – but as Coignier pointed out – when you overcome the technical difficulties you produce a new aesthetic – an enduring architecture. None of the houses shown here could have been built a hundred years ago and they do not look like the houses of a hundred years ago, but there is no doubt they have the basic qualities of architecture.