Projects and Features

Additions enhance City office block

A cantilevering feature entrance has been added

A former banking headquarters in the City of London is being converted into a new and spacious office development with additional new structural steel elements. Martin Cooper reports.

FACT FILE: 71 Queen Victoria Street, London

Main client: QV Unit Trust

Architect: SPPARC

Main contractor: Bouygues

Structural engineer: Pell Frischmann

Steelwork contractor: Graham Wood Structural

Steel tonnage: 600t

The redevelopment of 71 Queen Victoria Street in the City of London is a prime example of how steel construction can help revamp a tired old office building and quickly and economically convert it into a modern commercial building.

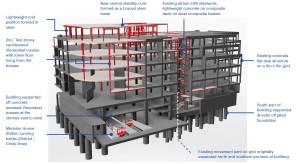

Main contractor Bouygues is updating the concrete framed former London headquarters of the Royal Bank of Canada by demolishing large parts of the original structure and replacing it with steelwork, resulting in the floor area increasing from 13,000m2 to more than 17,000m2. The scheme will also result in the seven-storey structure gaining an extra eighth floor with the addition of a rooftop pavilion overlooking St Paul’s Cathedral.

Work also includes a complete revamp of the main frontage of the building as well as further enhancements to the façades along Great Trinity Lane and Little Trinity Lane.

“The design of the building was bespoke and fine for a banking headquarters in the 1980s. However, the layout was unsuitable for a modern office building,” explains Andrew Murray, Pell Frischmann Technical Director.

The existing building is founded on two separate foundation structures with the northern portion supported on deep Vierendeel trusses above Mansion House London Underground Station. Consequently the building’s grid is defined by the spacing of the underground transfer structures resulting in a 6m grid in both directions.

The southern portion of the building is founded directly on piles, while a movement joint was provided across the floorplate effectively separating the two parts of the building. Pell Frischmann believes this was in order to allow the structure to accommodate potential differential vertical settlements between the two forms of foundation.

Working closely with Transport for London, the company says it was able to convince all parties that the movement joint was no longer needed since the old banking headquarters was constructed more than 30 years ago and differential settlement was no longer an issue. This meant new steelwork floors could be erected to join and knit the structure together and allow the new centrally positioned core to make the movement joint redundant.

Cost dictated that a complete demolition of the existing structure was not an option. Reusing as much of the original building was decided upon and this included the retention of the grid pattern.

“For convenience and ease of construction the new steelwork floors are based around the same grid, but by removing six old concrete cores we’ve de-cluttered each of the building’s floors creating the desired modern increased office space,” says Mr Murray.

The original structure was centred on two large atriums that have now been infilled with new steelwork floors. Additionally, a steel braced core has been erected in the middle of the building, accommodating six scenic lifts but more importantly providing the office block with much of its stability.

A cost-effective design option also extended to the building’s substructure and the reuse of the existing foundations. The only area of the project that has needed new piles to be installed is the core.

Reusing old elements of the structure is a very economic and sustainable objective, but any new additions to the structure’s frame needed to be as light as possible in order to avoid overloading the existing piles.

“This was why a steel composite design was chosen for the new parts of the building,” says Jonathan Cassidy, Bouygues Project Director. “Steel offers a number of advantages but its lightweight construction was the main benefit. We’ve been able to add new floor space and cores without increasing the overall structural weight.”

From the outside the most noticeable alteration to the structure is the new main entrance. Two 18m-long parallel two-storey Vierendeel trusses have formed a 6m cantilevering ‘bullnose’ feature.

The trusses were brought to site in four one-storey high sections, per level. They were assembled on the ground into two larger elements, before being lifted into position by a 70t capacity mobile crane.

“This was the only part of the steel erection programme which was erected by mobile crane,” explains Martin Campbell, Graham Wood Structural Project Manager. “The site doesn’t have a tower crane (box below) and space was tight all around the site with no room to park a mobile crane.

“However, for this part of our erection programme we were able to position the mobile just inside the site’s entrance and partially in the adjoining street for a weekend lifting programme.”

Bucking the trend of the small 6m × 6m grid pattern is the new eighth floor pavilion. A lightweight steel portalised 12m × 12m frame has been erected, delivering the new building a scenic top floor with views over the City and St Paul’s Cathedral.

“Rights to light issues prevented this new floor covering the entire footprint, but a steel frame added little extra weight to the entire scheme,” sums up Mr Murray.

Gantry gets building watertight

Once the demolition programme had been completed, getting the remaining structure watertight as fast possible was a major necessity.

Bouygues decided to install a gantry crane, straddling the central void, a machine that was then covered by a scaffold to create a temporary roof.

“This has proven to be a very cost-effective way of achieving both a watertight project and having a piece of equipment which could erect the new steelwork,” says Jonathan Cassidy, Bouygues Project Director.

“There is very little room around the site for a mobile crane and installing a tower crane would have left us with a large void in the centre of the structure which would have let in rainwater.”

All of the steelwork, forming the smaller central atriums, the associated floor plates, the rooftop pavilion as well as the new lift core have successfully erected by the 3.5t capacity gantry crane.

Steelwork contractor Graham Wood Structural delivered all of its steelwork to site on a just in time basis as there is no room for storage. The steel members never exceeded the gantry crane’s capacity and once on site beams and columns were immediately lifted into place.