50 & 20 Years Ago

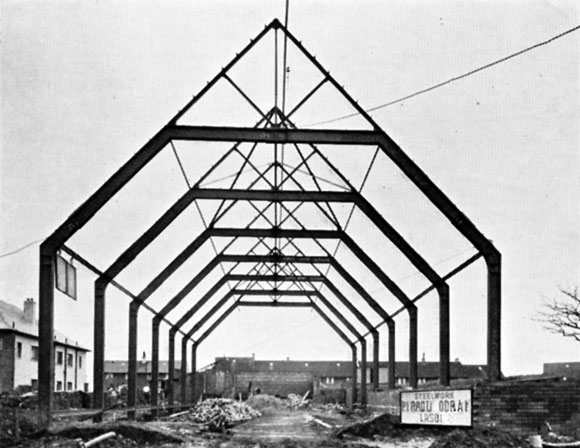

50 Years Ago: Steel for Ecclesiastical Buildings

From Building with Steel, May 1961

Structural steel framework for St. Conval’s Church, (Roman Catholic) Glasgow. Architect: A. McAnally, F.R.I.B.A. Glasgow

The imposing tower St Boniface’s Church, Stepney, London, E.1. Architect: C. Plaskett Marshall, F.R.I.B.A.

Temples and, later, churches were probably the world’s first architect designed buildings. Art flourishes best when dedicated and, once our ancestors had accepted the existence of spiritual values, men used their minds and imaginations to translate working skills into statements of faith; to infuse working materials with symbolic meanings.

Many architects believe that the design of religious buildings is not only the forerunner but is still the foremost of all forms of architecture. Most other structures command an impersonal respect or express a purely practical function. Religious buildings are deliberately designed to foster subjective feelings; to express in terms of art and craftsmanship, a communal devotion to spiritual values together with a community’s identification with the source of these values. Factories may become redundant, public buildings may fall into disuse, private houses may crumble or be relegated to the status of museum exhibits but a church is expected to last at least a thousand years.

Because of the strong emotions involved, religious architecture has aroused more hostility than – and has consequently lagged behind – architecture as a whole. A church is the structural embodiment of an emotional experience and those who share this experience tend to dislike ‘functional’ or ‘rational’ forms as they are understood today.

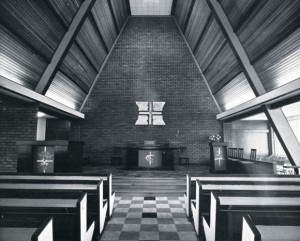

Interior of Park Church (Church of Scotland), Ardrossan, Ayrshire. Architects: James Houston and Son, Kilbirnie

Roman Catholic Church at New Malden, Surrey. Architects: F.G. Broadbent & Partners, London, W1. Consulting Engineers: Thomas Bedford and Partners, London W1

Indeed, there is no reason why they should accept these forms. The function of ecclesiastical buildings is spiritual, not practical. Equally, there is no reason why churches should be built in a hybrid of ‘traditional’ styles as if they were cheap furniture. There are no short cuts to venerability.

When an industrial community erects a church in the manner devised by their pastoral forefathers, tradition has been allowed to degenerate into theatricality and the result is morally and artistically unconvincing. Good architecture is based upon the honest use of materials and a true reflection of contemporary life – without descending to the decorative tricks which have debased the word ‘contemporary’.

The monumental grandeur of early churches are best matched, not by artificially massed effects, by a graceful arrangement of today’s fine building materials. A noble sense of spaciousness can carry more weight than massed solids.

Gracefulness is the prime advantage of steel as a building material for churches. Exposed steel members, in a proper spatial relation to the rest of the structure, form patterns of unsurpassed delicacy. A steel skeleton provides support for architectural expressions of surprising fluency. Rigidity is present, but it is confined to the strength of the material.

Because structural steel is strong a steel frame will endure for generations, standing patient and firm but proudly against practically all conditions: a testament to posterity of the spirit and matter of our times.