Profile

Small firm carves a big reputation

Successful small firms in the UK steel industry are invariably driven by a single character, often the founder of the company. Ty Byrd talks to one such founder, Jack Robertson, who describes what it takes to succeed as a small steelwork contractor.

To be small as a company in the UK steel industry offers the possibility of not just being beautiful but also manoeuvrable, flexible and highly responsive to clients’ needs. So says Jack Robertson who started his company – J Robertson & Co Ltd of Walton on Naze, Essex – 30 years ago and continues to pull in the work. What he does not say is that to exploit the benefits of small size you have to be an early riser, thoroughly commited, thoroughly competent and clever at business. Trustworthy and trusting too. Jack is all of these things and widely regarded as a player, never mind that he only employs 10 people.

“See this pile of documents, it’s a contract, for a large quantity of metalwork,” he says. “I’ve only just got it. Done some of the work already so it’s nice to see the paperwork.” Jack Robertson does not have shareholders to answer to, who might for instance want signatures on dotted lines before committing company resources. He goes on his own judgement and instincts, and is careful. His client in this case is absolutely blue chip, has been an employer of J Robertson for many years and its principals are known personally to him. “Us responding rapidly helped them out and ourselves, to win the job.”

Not that J Robertson has to go searching for work. The company is well known as a secondary steelwork specialist operating in certain niche markets and tender documents generally arrive as a matter of course rather than having been specifically sought. Sometimes a bid is not even asked for, the new work being offered on a cost plus basis. Trust is a two-way street, it seems.

Jack Robertson has built up a considerable reputation as a secondary steelwork specialist over 30 years

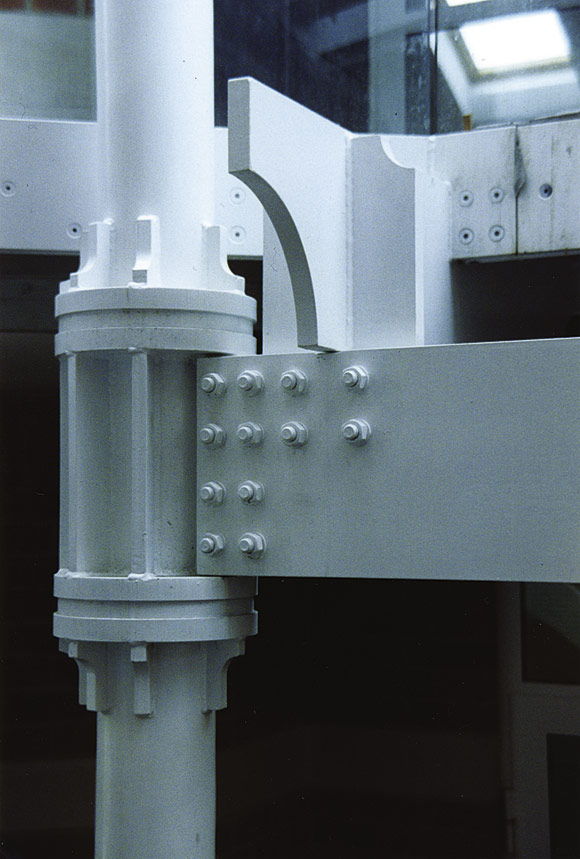

“Riser floors are a speciality of ours, open mesh flooring, staircasing, balustrades, architectural metalwork, anything with a bespoke nature,” Robertson says. The company also does “loads of structural steelwork”, although the impression he gives is that this kind of activity is not necessarily his favourite. “We do actually like the specialty stuff best, the metalwork that requires doing by hand, we’re good at it and not everyone else is.” And it is not just fabrication that J Robertson does but erection as well. Oh yes, and putting handles on saucepans and bottoms in coal scuttles occasionally, although such activity can bring problems.

The company operates in the east of England although it has carried out contracts as far north as Hull and as far west as Swindon in Wiltshire. It is London, though, which has provided much of the prestige work done throughout J Roberston’s existence, and Jack is able to reel off a list of high profile projects that have involved his firm: “Palestra in Blackfriars Road, Moorhouse where we did the risers and ancilaries, 90 High Holborn, Atlantic House, St Catherine’s House on Aldwych, Regis House by the Monument, Euston’s Triton Square and the Diamond Centre in Farringdon road, to name a few.”

Most of the activity in London is for Skanska whose City credentials are impeccable. (Skanska acquired the mantle of ‘London builder’ indirectly from Trollop & Colls, following T&C’s takeover by Trafalgar House, TH’s acquisition by Kvaerner and then Kvaerner assets going to Skanska.) “Skanska is a very good company to work for and the London emphasis for us with them is beginning to broaden. We are now working on schools outside town for the company following its PFI (private finance initiative) move into educational areas.”

In the east of England, J Robertson is currently working for big builders such as Higgins Homes and the Cadmun Group as well as a number of other companies. It has competitors — “new names are always appearing,” according to Jack — and not just its own size. The big boys sometimes go after quite small items of secondary work, when they have spare capacity. So how does J Robertson win? “On service, because we are an honest company and we can do what we say we can, on quality of work, on reliability.” He owns his own yard and overheads are not sky high.

Jack Robertson obviously gets a big buzz out of satisfied customers: “We’ve never had to go back to make good a job,” he says. “Our advice is often sought prior to a project which can give us a flying start in obtaining the work.”

Jack Robertson moved to Walton on Naze as a young newly married man in the late 1960s, attracted by the coastline and the inexpensive housing. He got employment with the local firm of Alderton & Sams which he describes now as “a glorified blacksmith”, learning all about metal from a clever craftsman called Dennis Polhill. There was a corporate lack of ambition at A&S that he found frustrating and after five years he started his own company, its first contract servicing a Trollop & Colls job in Colchester.

“There were only three of us and we’ve grown a bit since then,” he says. His two sons Tony and Colin work with him, both directors of the company and both extremely handy in workshop and on site. Will they take over from him? “I don’t know. I love the job, it’s my hobby, I’m often here at 6am and work until the sun is well down. I am not sure whether they would want that level of commitment.”

As this might suggest, Jack Robertson does not see himself retiring. “I’ve still got ambition and will probably die in my office,” he says.

One regret he will never have is moving to Walton on Naze. “It is a truly wonderful part of the world, with the most friendly people. I love it here.” A believer in giving something back, Jack is a local councillor and before that a retained fireman, sometimes rushing out from his yard in response to his bleeper to fight a blaze, leaving the works unattended and unlocked. “Nothing has ever been stolen,” he says.

‘Giving something back’ means being attentive to the locals, up to a point. “As a favour, we put a new bottom in this old lady’s coal scuttle and she asked what she owed. Well, it was two hours’ work but what could we charge her? I said 20p. In no time, three of her friends were around, all with worn out coal scuttles. I had to draw the line — you can’t run a business making consistent losses!”