50 & 20 Years Ago

Key Theatre

One of the latest additions to the growing number of theatres throughout the UK is the Key Theatre at Peterborough. Steel plays an important role in its structure and these notes by Joseph Robotham of Mathew Robotham Associates describe its main features. In addition the structural engineers, Space Structures Research Ltd, have added further information on the roof.

In 1967 a group of theatre enthusiasts met to discuss how they could bring back live theatre to Peterborough. They represented a very wide range of interests and included housewives, local councillors, the city librarian, representatives of drama and music groups and the writer. The thought common to them all was that no town could claim to be truly civilised without some form of theatre.

Peterborough, standing on the edge of the Fens, undecided whether to be part of East Anglia or the East Midlands; a cathedral city of 70,000 people had a good theatre tradition. Since the eighteenth century there had been at least one and often two or more theatres, sometimes in buildings which had to serve other purposes too; but always theatre in some form or other. In 1959 this tradition was finally broken when the Theatre Royal, a pleasant Edwardian theatre, was demolished to make way for a department store. This was in a period when the new television had swept the country and theatres. large and small, went down like ninepins. But even while this was happening a new breed of theatre was beginning to emerge. It came from the grassroots and was quite unlike the old dying commercial theatres. An example of this new kind of community theatre was near-hand at Boston, a small fenland port, with a population of only 20,000. A small group of people raised sufficient money to build an intimate theatre within the ruins of a medieval priory, right in the heart of the town. As well as the theatre itself the scheme provided meeting rooms, a bar, and exhibition space and was used by both professional and amateur companies. This was the model on which this group of people in Peterborough founded their own aims and what is more a strong stimulus – the feeling that surely if a small town like Boston could do it we could too!

First of all the aim was modest and this was to find a building suitable for conversion to a small theatre seating about 150 to 200 people. But no such building could be found so the aim expanded and we set about looking for a suitable site for a new building. It was a long search and when we eventually found the ideal site on the north bank of the River Nene there followed protracted and frustrating battles to persuade the city council to donate it to Peterborough Arts Theatre Limited which was a nonprofit-making charity. The difficulties were mainly planning and there was much talk of emigration and more fruitful things like gardening, but we stuck it out and the council finally, in 1969, agreed to lease the site at a peppercorn rent.

Setting aside the small matter of raising the money a brief was drawn up. The overall guiding aim was to provide a place suitable for all the arts, a building for all the community, young and old and a place to generate its own social activities. At the centre of the auditorium and stage, a single room concept to provide an intimate, exciting ‘theatre’ atmosphere, to encourage experiment in production and yet not inhibit more conventional theatre forms such as ‘box’ sets. The stage was to be as large as possible without a fly tower and the auditorium a single rake, seating 350-400 people with no seat further than 40ft from the stage. A spacious foyer/bar, suitable for exhibitions of paintings and making the most of the riverside and cathedral views. An entrance foyer with booking and manager’s offices, a coffee bar and a general purpose meeting cum rehearsal room. Backstage dressing rooms and a small scene dock but no workshops or administrative offices because it had been decided that the theatre policy would be to take in professional touring companies, amateur groups and to house a Regional Film Theatre. Later whilst the building was being constructed this policy was changed.

Because of the difficulties over the site, fund raising did not begin until 1969 when public response was tested by asking people to ‘promise’ to covenant or donate money to the project. The test was positive with an overwhelming and enthusiastic response and the committee decided that it was feasible to raise about £100,000. As both the quantity surveyor and the architect were members of the committee and joined the intrepid bunch of people who, every week, knocked on people’s doors asking for money it was made only too clear to us that economy of means was all.

The design was prepared, closely following the brief, treading warily between the many conflicting ‘expert’ theatre specialist views and opinions. The internal spaces, construction and finishes had to be as simple as possible and it was not feasible to be as lavish with space as one would have wished particularly in the front of house public spaces. An additional constraint was the free-standing nature of the building, set in an open park space with no back and nothing that could be hidden away as the public would have access to all sides of the building.

We had the courage (or we were foolish enough) to agree to start working drawings whilst fund raising carried on and the cost plan which had been prepared on the basis of the design drawings was strictly enforced. The site was made ground over the old river bed and the foundations were piled to a depth of about 27ft onto a rock bed. It was decided to use load-bearing brickwork generally, supported on a network of reinforced concrete ground beams supported on pile caps. The exceptions were the public areas where it was wished to ‘open up’ the building so that the activities inside would act as an advertisement and a sort of magnet for the theatre and here the structure is supported on r.c. columns. Ground-floor slabs are reinforced, generally 8/9in thick and tying in the ground beams, the first floor and roof slab to the main public areas are insitu concrete ‘waffle’ slabs using GKN plastic moulds and these are left exposed; the first floor to the dressing rooms is in p.c. concrete beams hollow pot; the stepped auditorium floor is in-situ concrete using relatively thin ‘L’ shaped steps spanning between raking beams and the roof to the dressing rooms, scene dock and plant room in timber joists with a lightweight decking.

Steelwork was the obvious choice for the auditorium/stage roof structure, although at one point timber was investigated in a further attempt to reduce costs, but it was just not feasible. From the design point of view it was felt that the roof structure should ‘honestly’ form a part of the theatre interior and steel, with its elegant possibilities, could do this economically. In addition, the roof had to accommodate the lighting catwalks and over the stage the grid for the support of lighting barrels, curtain tracks and scenic equipment. At the same time it had to be lightweight with the minimum amount of thrust on the 15½in brick walls which were 24ft high. Several designs were enthusiastically prepared by the consultant Wittold Stepien (whose axiom was that ‘this is not a cowshed but a theatre’ and perfection was the point at which one stopped) using various forms of space frames but though they would have undoubtedly looked very elegant great difficulties were experienced in fitting in the lighting catwalks and too we felt that we were stretching the medium too far; so they were reluctantly abandoned. The design eventually agreed was a series of very straightforward and simple trusses, in r.h.s. sections, assimilating all the technical requirements and impeccably put together. The roof decking is in lightweight p.c. concrete units, finished outside with blue/black asbestos cement slates.

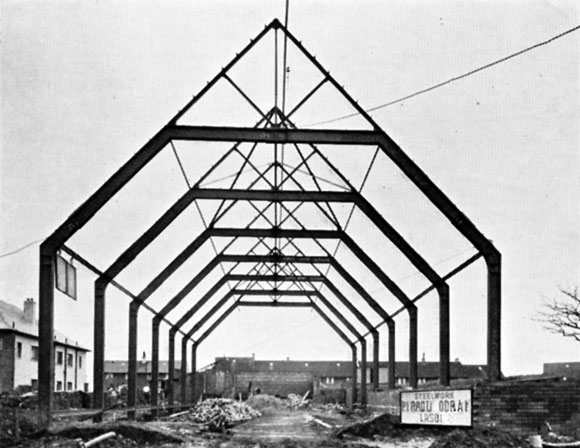

Final choice of 7ft deep tubular steel trusses for the octagonal heaped roof for Peterborough Arts Theatre was dictated by the position of the stage spotlights which were to be fixed to the catwalk railings and the run of large circular exhaust and heating ducts over the stage and on both sides of the auditorium, which had to be incorporated in the depth of the roof structure.

In addition to these requirements the steelwork above the stage had to carry the suspension system for the curtains, scenery and cyclorama, allowing equipment to be slid by pulleys to any position on the stage. As the steelwork would be exposed to public view it was necessary to design the structure in a simple form to combine the dual function of supporting the roof cover and theatre equipment on single members of uniform appearance. Therefore the top booms of the trusses, tubular purlins on the sloping side of the roof and the joists over the stage are all 4 x 4in sections and the corner hip purlins are back to back 4 x 2in RHS or channels.

Great care had to be taken to incorporate all bolt connections inside of tubes and to cover openings with plates welded on site. On the joists and channels, stud bolts were welded to sections. Studs were welded to channels and angles for connections with the lags welded to main trusses, thus obscuring nuts to view.

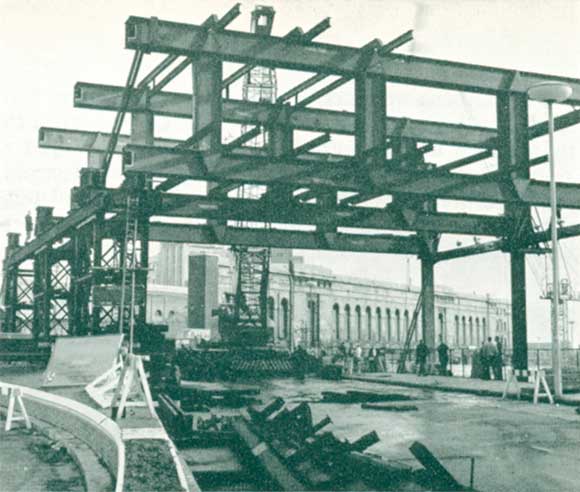

A trial erection of the roof structure and the catwalks was arranged at the factory beforehand in order to ensure proper alignment of the connections and to facilitate erection on site. This was carried out in four days with the assistance of a 15-tonne hydraulic crane with 15ft jib.

I was apprehensive that when the theatre was opened there would be a lot of criticism of the exposed roof structure because of associations with industrial-type buildings and the fact that theatres are still connected with an Edwardian-type elegance and luxury. But in fact not a word of condemnation. The intricate shapes formed by the members of the trusses, with the catwalks (with their stage light fittings) and red tubular ventilation ducts, the dark blue of the roof in fact seem to heighten the excitement and theatre atmosphere of the auditorium. In addition, the fact that the steel roof structure can be seen to pass over the stage helps enormously to unify the auditorium with the stage – one of the most important aims of modern theatre design.