Projects and Features

Island’s healthcare gets a boost from steel

Getting the steel supply to the island was a logistical challenge which had to be overcome before construction work could begin on an extension to Guernsey’s main hospital. Martin Cooper reports from the Channel Islands.

FACT FILE: Princess Elizabeth Hospital, Guernsey

Main client: States of Guernsey

Architect: Nightingale Associates

Structural engineer: WSP

Main contractor: Charles Le Quesne

Steelwork contractor: Hambleton Steel

Project value: £27M

Steel tonnage: 650t

One of the most important public works projects under way on the island of Guernsey is the expansion and redevelopment of Princess Elizabeth Hospital.

Originally built in the late 1940s, the hospital, which is the island’s largest, is undergoing a phased modernisation programme, with a new £27M clinical block representing Phase 5.

Scheduled to open in 2009, the new block is being built on ground previously occupied by hospital staff residences and a car park. The previous phase of hospital construction work saw a new staff residence block – John Henry Court – built, and its completion enabled the old building to be demolished, freeing up land for Phase 5.

The new three-storey block has a total floor area of 11,000m² and connects into the existing hospital building over two levels.

“When we initially came on site in January 2007 the first job was to dig out and level the ground,” explains Alan Rogers, Project Manager for Charles Le Quesne. “There was a very significant earthmoving operation as we had a sloping site which then meant we needed to install a large retaining wall.”

Piling work commenced in March and concrete pad foundations were installed to accept the steel columns.

When it came to designing the new hospital block, Project Architect, Simon Boundy, says marrying and tying the new structure into the existing hospital was of paramount importance.

“This phase is the largest and the driver for the whole redevelopment, consequently we wanted the structure to make a contemporary statement.”

The existing hospital buildings are steel framed, so using steel meant marrying together the same framing material at the point where the blocks meet.

Jamie Siggers, Associate at WSP, says tying the new build into the existing structure was a challenging aspect of the design and required some tricky solutions. “We had to thread the new steelwork into the old building, while avoiding all services.”

Vibration can sometimes be an issue, especially on hospital projects, but Mr Siggers says all concerns were thoroughly checked with SCI guidelines. “Sway wasn’t an issue either,” he adds. “As steel bracing on all floors takes care of this.”

“The overall design and the need for varying room and ward sizes meant steel was the obvious choice,” says Mr Boundy. “And, in some areas the steel columns are left exposed as architectural features, and this wouldn’t have worked so well in concrete.”

The contemporary design will also be achieved by the block’s distinctive cladding which is a combination of terracotta rainscreen, zinc and timber cladding, together with some large glazed areas. This exterior design mirrors the recently completed, and adjacent, John Henry Court.

Once steel was chosen as the framing material, steelwork contractor Hambleton Steel then had the logistical problem of getting the material across the English Channel to Guernsey.

As with most construction jobs undertaken on the Channel Islands, the majority of materials have to be brought in from the mainland. This involves close cooperation with the shipping agents and means a lot of thought needs to be given to delivery batches.

“We’ve done jobs in Guernsey before and we basically refined our procedure from a contract we did earlier this year,” comments Andrew Fixter, Project Manager for Hambleton Steel.

Hambleton sent batches of erectable loads, but also split these loads down into smaller batches. One containing steel members of less than 6m lengths and another with the sections longer than 6m. This procedure was worked out with the shipping company and was considered to be the optimum way of loading the goods onto the ship at Portsmouth.

“Once we’d got the steel batches onto a ship we had to make sure it could be erected almost immediately.” adds Mr Fixter. “The hospital site is quite confined with little or no room for storing materials.”

This meant close cooperation between those sending the batches from Hambleton’s Yorkshire fabricating yard and the steel erectors on site in Guernsey.

“We had some leeway as the shipping company would allow us to leave some steel sections at the port in Guernsey, for a while,” says Mr Fixter. “But essentially everything was sent in loads which were then immediately erected.”

Accuracy was a key element of Hambleton’s steel delivery and shipping process and Mr Fixter says it ‘worked like clockwork’ during the company’s 20-week steel erection programme.

Mr Rogers agrees and says the sequence worked out between Hambleton and the shipping company was vital to the successful steel erection. “The majority of construction materials come from the mainland and a good working relationship with the shippers is important.

“The beauty of steel is that it can just be brought to site and then put up and bolted straightaway,” he adds.

As the construction site is next to a functioning hospital noise and traffic movements need to be kept to a minimum. Steel deliveries were generally restricted to one a day early in the morning to avoid heavy traffic and cause the least disruption.

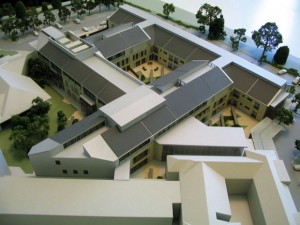

Overall the building is formed by two conjoined T-shapes in plan, which then form two enclosed inner courtyards.

One courtyard is completely within the new building, while the other is formed from the new block and existing structures.

“The courtyards are essential to the design as they provide quiet areas for patients to sit and recuperate,” explains Mr Boundy. The hospital wards then wrap themselves around these courtyard areas, with most floors having views into these landscaped gardens.

The layout of the building’s three levels are: ground level, outpatients, wards and private rooms; first floor, wards and private rooms; and second floor, training area and plant rooms.

One of the main features of the new block is the ward and private room layout. A Nightingale designed four-bed bay cruciform layout has been used for all wards. “This gives each ward a reasonable amount of individual privacy,” explains Mr Boundy.

The building’s uppermost level is topped by a feature mansard roof which incorporates some external plant areas. Flat areas within the roof were considered the best fit for plant as they won’t be visible from ground level.

The top floor will be used as a staff training area and one continuous column free area was needed. “It was these long span areas that best suited the use of steel,” adds Mr Boundy.