Profile

Grimshaw grows in strength from succession

Grimshaw’s Ijburg Bridge has become a symbol for a regenerated area of Amsterdam (Photo: © Jan Derwig)

Once seen as the new kid on the block with a Meccano set, Grimshaw is now a mature, internationally acclaimed architectural practice. Managing Director Chris Nash tells Nick Barrett about plans for the next stage of development.

Succession problems have been known to dog the most successful of companies, as the retirement of founders can deprive those left behind of their driving force as well as original inspiration. No such problems are being seen at Grimshaw, one of the biggest architectural practices in Europe whose eponymous founder, Sir Nicholas Grimshaw, has retired from full time involvement in the practice to devote himself to the Presidency of the Royal Academy.

When Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners first made the headlines with the Camden Sainsbury’s in 1986 the practice was only six years old. Under a new Board of Directors the 25 year old practice is going from strength to strength with the Grimshaw ‘brand’ continuing to gain recognition among clients and professional colleagues. Managing Director Chris Nash says Grimshaw is now a mature firm, albeit one which is undergoing a rapid process of change, but he admits he was worried that clients might assume that the retirement of Nick Grimshaw would spell a weakening of the practice.

Below: Rolls-Royce appointed Grimshaw to design its Chichester headquarters and plant (Photo: © Edmund Sumner/VIEW)

Bristol University architecture graduate Nash, who joined when Grimshaw was only six people strong, says the firm is well established in its key markets – transportation, workplace, university and what he calls ‘community’ projects for arts, leisure and mixed use. “But we had to emerge from the idea that the practice was a one-man show,” he says. “Clients have been encouraged by the steps we have taken to ensure the continued development of the business and they can see we are here for the long term.

“Nick Grimshaw is still a presence at the practice, albeit part time, and we have a structure in place which will ensure the future of the business regardless of who is at its head.”

One guarantee for the future concerns ownership; Grimshaw is 49% owned by its directors and 51% by the staff through an employee benefit trust. Four of the Board are current shareholders and plans are in place for the four new directors to join them. So Grimshaw cannot be bought or sold, or floated on the stockmarket against the interests of the employees.

Still based at the firm’s original office at Conway Street in London’s ‘Fitzrovia’, the firm has expanded into adjacent offices and now houses 90 staff in London out of a total of 130 worldwide. There are thriving offices in Melbourne, and New York. Although Grimshaw appears about 40th biggest in the UK when ranked by size, it is in the top five by reputation among other architects, according to surveys.

The business plan envisages an organic expansion over the next three years in the existing key areas to employ 180 staff. The practice also includes an industrial design business. Alongside Nash as Managing Director of the Group are regional Managing Directors dedicated to the Americas and Australasia, and other Directors overseeing specific business sectors. There was a Berlin office but this has been closed even though Germany remains a key market. “Berlin is as easy to reach as Cornwall,” says Nash, “so we are happy to service the European market from London.”

Grimshaw is a major presence on the international scene, with some spectacular projects currently on the books as well as a long list of completed internationally acclaimed successes. Grimshaw first came to wide notice with designs for buildings that showed an appreciation of engineering and the desire to make the workings of structures apparent. The approach first achieved international acclaim when the Eurostar International Terminal at Waterloo opened in 1992, and can still be seen in many of the projects currently on the books.

Nash seems equally at home talking engineering as architecture, but he is adamant that: “We are architects, not engineers.” The firm is heavily oriented towards transportation, like rail and airport terminals. Twenty years ago the workload was mostly workplaces and this remains a key area, although mostly large office buildings rather than factories. There is a strong presence in the university sector, with four projects currently underway in the UK, at University College London, London Southbank University and the London School of Economics.

There is a specialisation in what Nash calls ‘community buildings’ like the famous Eden Project in Cornwall, and the conservation and visitor centre for the Cutty Sark. In Spain the steel framed £22M Fundacion Caixa Galicia art gallery has just been completed in La Corunna. The practice has been appointed as architects for the Battersea Power Station redevelopment in London, a major mixed-use scheme.

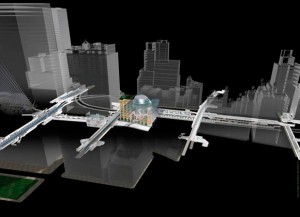

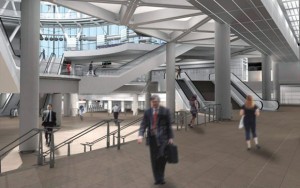

One of the most impressive projects on the books is the £436M ($750M) Fulton St Transit Center in downtown New York. The project will house for the first time in a single concourse nine subway lines currently using six stations, using a 34m high asymmetrical tapered triangulated steel structure supporting a central dome to take sunlight to the lower levels.

In Melbourne, the Southern Cross railway station is being covered by an undulating roof whose form was suggested by winds in the surrounding desert. “It is the biggest tubular steel job ever done at this tolerance in Australia,” says Nash.

What is it that sets Grimshaw designs apart? Nash says they are characterised by a clearly legible structure, innovation and a rigorous approach to detailing. ”The buildings need to have spatial and organisational clarity, reflecting the activities to be carried on within them, and be flexible enough to respond to changing needs,” he says.

A common interest in making things and in how things are made seems to run through the practice. Nick Grimshaw himself was once dubbed ‘High Priest of High Tech’ because he liked his designs to show rather than conceal how the buildings were supported. Grimshaw architects are technically minded as opposed to the fashionable stylistic bent of many architects, which is seen in the practice’s reputation for research and application of new materials and construction techniques.

Nash says the technical interest of architects goes back to the craftsmen of the medieval days. With the industrial revolution engineers became interested in finding new forms of building to house the new industrial processes. They had to ask themselves what a railway station should look like, for example. The first ones looked like country houses, but other answers came later.

These are still questions architects like to ask today, he says, and their answers are what takes design forward.

“Our architecture is about building, not theory,” says Nash. “Our buildings are bespoke and special; we like to think, listen, challenge and collaborate to get to the core of the problem. Our products come from the process that forms them.” Grimshaw is also interested in space and light and how they interact in buildings. The Fulton St terminal in New York is all about admitting light, sunshine and air. “We are also very interested in how big buildings fit into towns,” says Nash, “and in how large numbers of people use public buildings; Zurich airport terminal for example provides a comfortable space where people can choose to sit and look at the aeroplanes.”

Buildability is another hallmark of Grimshaw designs, Nash says. “We work closely with the builders on our projects. We are proud to have a good reputation for that among contractors like Bovis and McAlpine. We also know the steelwork contractors well and like to get involved with them as early as we can in a project.”

Grimshaw designed buildings tend to make great use of steel. Nash says: “As architects we have no predisposition to any material. Economics sometimes dictates that you use steel, and the advantages of steel are well known. Tall buildings for example will almost always be steel. We value steel for the fact that sections can be prefabricated, so quality is high and finishes are of high quality. The need for fire protection is a cost disadvantage but new coatings are helping. Also there is an increasing concern for sustainability and the benefits of steel’s low embodied energy and recyclability over concrete are well known.”

Nash says that the United States and Australia make even greater use of steel than the UK. The key is to use the appropriate material, whether it is steel or timber or whatever. As a Structural Steel Design Awards judge in 2005 Nash was pleased to see private houses designed in steel being put forward for awards, as well as the use of steel in large and high-rise projects.

“The building usually suggests itself what material should be used,” he says. “When we use steel we can choose to increase the transparency of a structure. We design structures to be as light and as visually permeable as possible, whereas with timber for example you might try and celebrate the heaviness.”