50 & 20 Years Ago

Clad in Cor-Ten

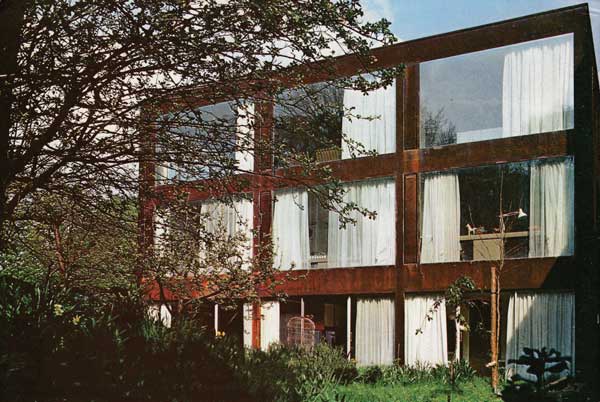

In this article Valerie and John Winter describe the house they designed for themselves and their family. It is interesting as being the first application of Cor-Ten to a private house in the UK.

This is the second house we have designed for ourselves, and experience of living in the first one taught us to know what we wanted – lots of space, lots of light and outlook, yet privacy. During the seven years that elapsed between the designs of the two houses we had three children, and it is largely on their account that the second house is three and a half times the size of the first.

Site

The site is the north part of the garden of a house originally built for the Superintendent of Highgate Cemetery, and the great stone capped brick wall which surrounds the cemetery goes round our site, giving us privacy and acting as a retaining wall for the garden which is six feet higher than the road. The western part of the garden has mature apple trees, and although these now touch the house, the builders were careful and the trees were not damaged in the building process.

Planning

Fine views from the top and the need to keep as much garden as possible led to a three-storey house; and as the roof terraces of the previous house had been a source of worry with the children, the upper floors of the new house were to be sealed. Requirements for two living-rooms, dividing activities on a quiet/noisy basis determined the internal layout.

Only the ground floor relates to the garden, and this is emphasized by an earth-coloured quarry-tile floor at the same level as the outside ground. Two-thirds of the ground floor is the place where it all happens – record playing, cycling, model making, eating, cooking, shouting, music practice and the rest; in good weather the floor is opened out on to the garden, which because of the surrounding wall becomes part of the house. Also on the ground floor, and with its own outside door, is the spare room with adjacent bathroom which can be au pair’s room, granny flat, teenagers’ den, or rented off as the need arises.

The middle floor is the sleeping floor and acts as a buffer between noisy ground floor and quiet top floor. The bathroom is large and doubles as a laundry; children’s clothes are stored here and sorted on a long low bench under the window.

The top floor is open with a central fireplace separating the living area from the place where we both work. This floor is basically a calm quiet area for us, but it serves, like a Victorian parlour, as a place which is usually civilized, no matter what noisy entertaining is being carried on elsewhere.

Garden

The site always had that quality of a slightly abandoned Victorian country garden; we have tried to keep that ambience but amend it to work better for children – areas paved with old bricks, rough grassy banks with the indigenous bluebells and cow-parsley growing in profusion. An outside table and benches enable instant use to be made of any good weather and saves having to clear up after children’s meals – the foxes come and polish off the scraps! The site includes a partly filled-in tunnel through which Karl Marx, Herbert Spencer and all the others were carried to their graves in the east part of the cemetery; now abandoned and overgrown, it is a magical adventure playground, officially out of bounds to children, but sneaked into to bring back caches of marble chippings once intended to decorate a tomb.

Construction

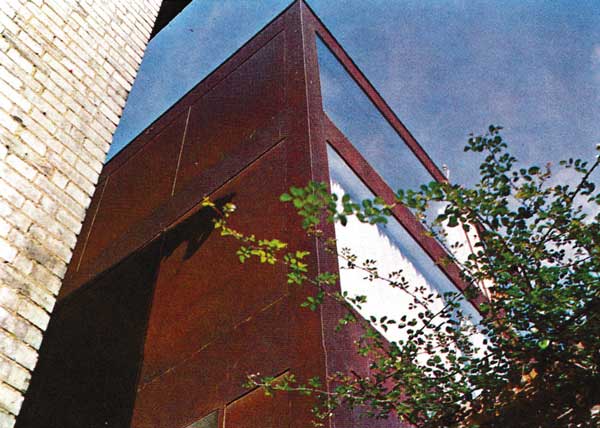

We built in steel because we wanted some open floor areas, because we might want to change the internal layout, because we feel fenced in by solid walls and because of the discipline it gives to a plan. For a house of this size and quality, the cost of a steel building was about the same as a brick building because the budget had to carry research costs (no one knew of a glazing mastic that worked with Cor-Ten). Also we often had to design with the materials we could get, not with the materials we wanted. Costs should be lower with steel as experience widens and materials become more readily available.

The twelve-foot-bay size relates to the 4ft width of so many building materials, to the standard sliding doors on the ground floor and to the maximum span of the channel reinforced wood wool roofing slabs.

ln England, unlike America, the cold season is a damp one, so steel structures will run with condensation unless they are either wholly external or wholly within the heated envelope of the building. Our structural frame is internal, it has three 20ft x 12ft bays, with 6in x 6in columns and 10in x 4in beams which in some cases have short lengths of mild steel channels welded to their top flanges so that they form the tension boom of a composite beam with the concrete floor slab as compression boom – an arrangement which keeps the floor beams shallow and enables similar depths of beam to be used everywhere without the lightly loaded edge beams being unduly oversized. Outside the mild steel structural frame is 2in insulation and then ¼in Cor-Ten A plates welded together to form a continuous cladding system to the frame. Double-glazed panels and fixed wall panels are theoretically interchangeable and the wall panels consist of 12 gauge Cor-Ten A sheet steel bonded to Asbestolux panels, and, like the glass, these panels are pressed in behind the steel facings to the frame, set in Rubboseal mastic and secured internally with a mild steel angle.

Ventilation to the upper floors is by storey height flaps of 12 gauge Cor-Ten A-faced polyurethane foam panels set in galvanized universal steel window sections closing on to a neoprene strip, these flaps are centre pivoted so that the widest opening is 5in and no child can fall out and no intruder can get in. Cor-Ten is surely the first modern building material that stands up to the rough use a building gets; it is left to weather, and to prevent the weathering becoming too uneven all projections and recesses have been kept to within ½in. A splayed quarry-tile plinth at the base of the house accepts the stained run-off water before the Cor-Ten has developed its final patina.

The top floor of our previous house was of lightweight construction and we had experienced some discomfort from rapid solar heat gain and from condensation. To obviate this situation we needed a thermal flywheel inside the insulation so whenever the choice was open we have chosen mass-screeded roof, concrete floors, concreteblock partitions, massive fireplace, and all external wall panels are backed with 1 ½in polyurethane foam, then 4in concrete block; the ambient internal temperature now changes slowly, and enables off-peak electricity to be used for heating, coupled with a fan-assisted booster on the top floor controlled by an external thermostat.

Furnishing

Finishes on the ground floor are tough, for, apart from family wear and tear, our downstairs living-room serves as a play group for twenty toddlers every Thursday.

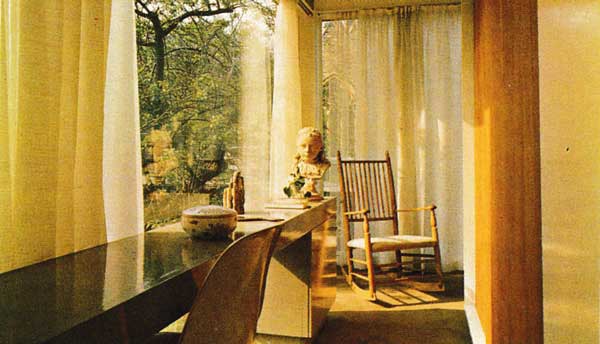

The carpet begins at the bottom stair and signifies that the upstairs environment is to be treated with more respect; children’s rooms have cork walls for pin-ups and a bench across the window so that things do not get piled against the glass. The top floor living-room has the most beautiful furniture we could find.

Curtains everywhere are white terylene, and are not seamed so that they can be washed in manageable armfuls and drip dried; the curtain tracks are fixed to the underside of the steel to emphasize the frame.

In choosing the furniture, as in the design of the house itself, we have tried to avoid anything trendy, and to make decisions which will still seem right when the mortgage is paid off in 1994.

Architects: John Winter & Associates.

Structural Engineer: Herbert Heller