Projects and Features

A steel framed jewellery box

One of the most ambitious heritage projects in recent times is underway at Portsmouth Dockyard. Martin Cooper reports on the construction of the finely crafted permanent home for the Mary Rose.

FACT FILE: Mary Rose Museum, Portsmouth

Main client: Mary Rose Trust

Architect: Wilkinson Eyre Architects

Interior architect: Pringle Brandon

Main contractor: Warings

Structural engineer: Gifford, part of Ramboll

Steelwork contractor: Rowecord Engineering

Steel tonnage: 400t

Project value: £35M

Described as one of Britain’s most important archaeological finds, King Henry VIII’s naval flagship the Mary Rose, will soon be housed in a new purpose built museum alongside thousands of objects which were salvaged with the ship’s hull in 1982.

Since being raised from The Solent thirty years ago, the remnants of the ship and its artefacts have captured the public’s imagination and thousands visit the current museum in Portsmouth Dockyard every year.

The preserved objects offer a unique insight into the life and times of a Tudor warship as many of the artefacts have remained unscathed since the fateful day in July 1545 when the Mary Rose sank.

About 1,000 of the 1,900 recovered objects are currently on display in the existing museum – the new facility will have more space for exhibits – while the hull itself has been undergoing preservation work, housed in a temporary structure in a nearby dry dock.

The project, largely funded by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, will see the Tudor warship finally ensconced in a permanent building, positioned over this dry dock in which the Mary Rose currently sits.

For the Mary Rose Trust, the project represents a dream come true. “It will combine the two halves for the first time,” says the Trust’s Chris Dobbs. “Visitors will soon be able to view the preserved hull right alongside many of the ship’s objects.”

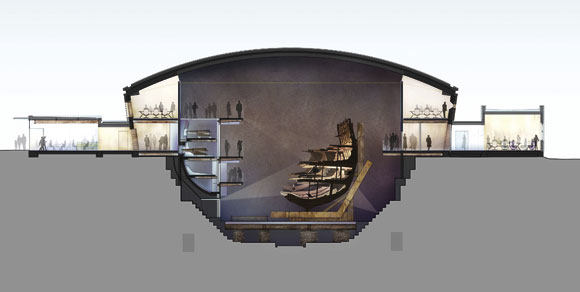

Having won a design competition in 2004, Wilkinson Eyre and Pringle Brandon’s concept revolves around the preserved starboard portion of the hull sitting in the middle of the new boat-shaped structure. A sort of pearl within its oyster shell, as architect Chris Wilkinson describes it.

Within the museum there will be three visitor galleries, corresponding to the principal deck levels of the ship. These will run the length of the building, imitating the missing port side of the vessel and allowing the original artefacts to be displayed in context.

All through the construction process the hull has remained in the middle of the project, in its ‘hot box’ – a tent-like structure in which air-drying is proceeding, a conservation process which will not be completed until 2016. Until then visitors will be able to see this process through viewing ports positioned along each of the gallery levels. On completion of the air-drying phase, the ‘hot box’ will be removed, allowing visitors new and dramatic views of the ship’s original timbers.

The new museum has also been described as a finely crafted, wooden jewellery box, as it will be clad in timber planks both reflecting the structure of the original ship and the nearby HMS Victory. The planks will be painted black and inscribed with carvings used by crew to identify their personal belongings.

Constructing a building which not only encases the ship’s hull but also the dry dock in which it nestles has thrown up a number of construction challenges. The dock itself is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, so there was a requirement for minimal interference to the original stonework. Something lightweight was needed; a structural frame which could also span the dock without interfering with the conservation work going on in the midst of the site.

“The complex shape of the structure and the need for a lightweight solution meant steel was the only real choice,” explains Ben Rowe, Gifford Technical Director.

The building’s main steel columns sit on pads, which are isolated from the dock’s stonework by a structural membrane. The pads not only protect the dock but also distribute the structure’s loads evenly.

From the dock the steel frame rises up and encloses the hull in an elliptically shaped structure. The frame also includes two pavilions, on the north and south side of the structure, one will house the entrance foyer while the other will accommodate an educational suite.

The building’s irregular shape has been formed with a number of faceted columns which rise outwards from the pads and then rake inwards to create the appearance of a ship’s hull. The crank or change in direction happens at a number of multi-connections, positioned approximately 3m from ground level, a point which is nearly a third of the way up the building’s side.

Each of these hub connections, designed by Rowecord Engineering, not only accept the two columns sections, but also cross beams, floor beams and tubular bracing. All of the connections were prefabricated off-site and this ensured these complex pieces of steelwork arrived at the project in the required exact configuration.

The main columns forming the building’s rib cage are spaced at 5m intervals, while the internal columns are spaced at 3m intervals, a width that means these structural bays match the original size of the Mary Rose’s gun ports.

Inside the completed museum, galleries corresponding to deck levels will seperate the hull from the ship’s objects

“Steelwork was erected one bay at a time, using some temporary propping,” explains Nicolas Beausseron, Warings Project Manager. “However once the bracing, which is curved to match the perimeter shape, was installed, each bay was stabilised, allowing the next bay to be erected.”

More steelwork is connected to the perimeter columns, to form the visitor and object galleries that encircle the museum’s interior. The visitor galleries curve, to mimic a ship’s deck, and these were formed by staggered beams supporting the flooring.

The lower ground floor of the museum houses not only the hull’s ‘hot box’ but also an array of necessary equipment and plant for ongoing conversation work. So as not to interrupt the important work taking place, two large trusses span this plant area, forming a large column free zone.

“Prior to installing these trusses a crash deck was installed, during the enabling works, to protect the equipment,” says Mr Beausseron.

Interestingly, when the conservation work is complete in 2016 and all of the equipment is removed, this area will become a new public gallery. Positioned at lower ground floor level, it will offer visitors another view of the unwrapped hull.

Topping the boat-shaped museum is an elliptical roof, which was prefabricated off-site and lifted into place over the dock, again minimising disruption to the conservation activities and following a precise methodology to reduce the risk of objects falling on to the hull. Supporting the roof are a series of 32m-long curved rafters, installed in three sections, to avoid having to work and bolted up the steelwork above the ‘hot box’.

Steelwork erection and the installation of the roof was completed during August. Internal fit-out has now started with the museum scheduled to open at the end of 2012. Meanwhile, preservation work continues apace on the Mary Rose hull and it will be carefully dried out within the new facility until being finally unveiled in 2016.