50 & 20 Years Ago

50 Years Ago: Structural Steel in the Nuclear Power Industry

Structural steel is marching with the times. Nuclear power stations – virtually unthought of a decade ago – are consuming large quantities of structural steelwork in both new and traditional applications. Windscale, Britain’s first large venture into the atomic energy field, used 17,000 tons; the atomic factory at Capenhurst used an initial order of 20,000 tons and then called for more in order to extend; at Dounreay, more that 5,000 tons were used. The ‘true’ power stations now being built are using even more, and for purposes varying from conventional girder structures to mammoth cranes as tall as Nelson’s Column.

THE EARLY DAYS…

Like so many things invented by man, the first nuclear reactors were built for warlike purposes. The USA employed the first ones to produce military plutonium, and Britain’s first atomic plant – at Windscale – was built for the same reason.

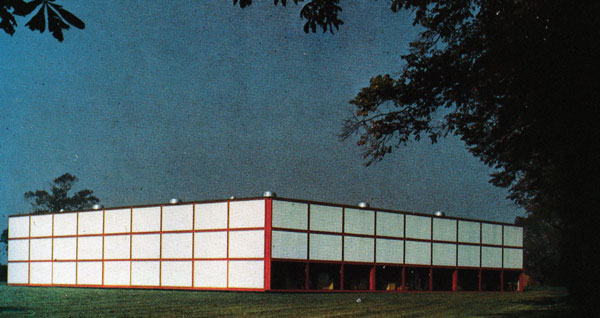

Calder Hall saw the beginning of the nuclear electricity era: the electricity here being a secondary product of the plutonium plant. That was just over three years ago. Today a new power station at Chapelcross, the first to be built primarily as a power station, is in operation. Others, in differing stages of construction, are going up at Bradwell, Berkeley, Hinkley Point, Hunterston and Trawsfynydd. Britain is now well on the way to achieving the generating capacity called for in the 1955 White Paper: twelve stations generating between 1,500,000 and 2,000,000 kW by 1965.

WINDSCALE AND DOUNREAY…

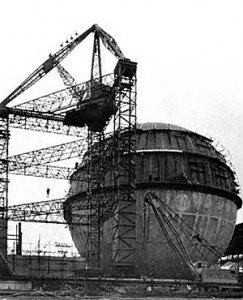

Large though it is, Dounreay’s containment sphere is dwarfed by the giant crane used during its construction.

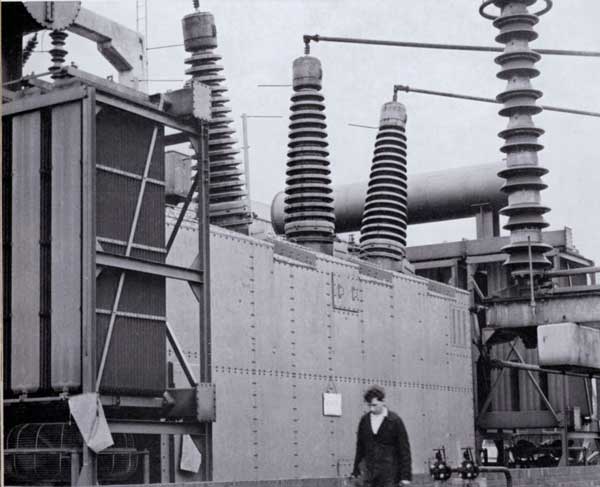

Seventeen thousand tons of structural steelwork: that was the first indication industry received of the quantities likely to be required by the programme and was the amount employed in the buildings and other structures at Windscale. Although Windscale produces plutonium and not electricity, it is important in that it was the first large-scale unit built in Britain’s military programme in this field. The buildings are conspicuously different from those at a civil nuclear power station, the site being dominated by two giant chimneys each 414 ft. tall. On top of each of these is a 200-ton steel filter assembly – rather like storks nests.

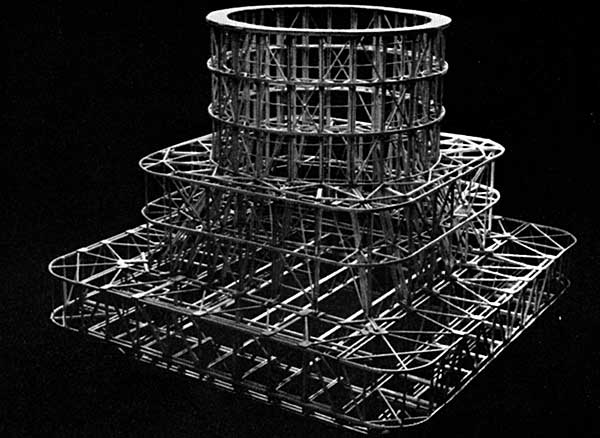

Dounreay is capable of contributing 15,000 kW to the National Grid. It was built primarily as a fast breeder research station and, like Windscale, differs considerably from conventional power stations in appearance. Here, everything on site is dwarfed by the containment sphere. Five thousand tons of structural steelwork were used at Dounreay, much of it in connection with this sphere. The steelwork was used principally in the form of lattice-type straight and radial girders, floors, columns and crane girders. The seven-floor active element store building – 86ft high by 55ft by 66ft – is of beam and stanchion construction; it has seven floors, some of which are chequer plated.

To the west of the sphere is the heat exchange building, also of beam and stanchion construction. This has five floors, four of which are chequer plated, with castellated beams at one of the floor levels.

THE GOLIATH CRANE…

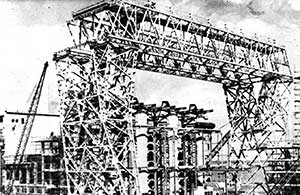

Structural steelwork being erected round Bradwell’s insulated boilers, here framed by the 187 ft span of the Goliath crane.

Besides being used extensively in the permanent structures at power stations, structural steelwork is also called upon to fulfil equally vital but temporary roles. For instance, a great deal of heavy lifting work has to be done to instal reactor and other vessels. Conventional cranes cannot cope with the loads and heights involved and special forms of lifting gear have been devised to carry out this work. Typical of these is the Goliath crane used at Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex. This is of the overhead girder type, and is supported at each end by a leg mounted on eight four-wheel bogies. The crane straddles the reactor building during all stages of construction and is designed to lift 200 tons to a height of 140ft; an auxiliary hoist can lift 30 tons.