Projects and Features

Curtain rises on steel classic

Changing the design of Shrewsbury’s Theatre Severn from a concrete frame to steel frame resulted in a number of benefits, such as speed of construction and cost effectiveness, which all helped produce a structure the town is rightly proud of. Martin Cooper reports.

FACT FILE: Theatre Severn, Shrewsbury

Main client: Shrewsbury & Atcham Borough Council

Architect: Austin Smith Lord

Main contractor: Willmott Dixon

Structural engineer: Curtins Consulting

Steelwork contractor: Midland Steel Structures

Steel tonnage: 800t

Project value: £20M

Shropshire’s county town of Shrewsbury is now home to a new eye-catching waterside theatre that since officially opening in March has been regularly packing in audiences. Located on the banks of the River Severn at Frankwell Quay, one of the main gateways into the town, the theatre has quickly enhanced Shrewsbury’s reputation as a regional centre for cultural and leisure opportunities.

It has been a while coming, as the idea for a new theatre was first mooted more than 40 years ago. The project came very close to being approved on a number of occasions, various sites and building designs were put forward over the years, and the final approved design was even altered at the last moment.

Initially the approved design was a concrete framed structure, however main contractor Willmott Dixon tendered an alternative bid with its own design team. Working alongside architects Austin Smith Lord and engineers Curtins Consulting, a steel framed solution was tendered and accepted, which generated significant cost savings to both the superstructure and substructure. Acoustic and dynamic performance were analysed carefully to ensure the steel frame was acceptable.

“Speed of construction and cost effectiveness were the main advantages associated with the steel design,” explains Harry Dhanjal, Operations Manager for Willmott Dixon.

Ashley Davies, Director at architects Austin Smith Lord agrees and says: “There were a number of reasons why a steel frame was more viable for the project. The spans for the main performance areas suited the use of steel trusses, while a lighter frame in general sits better on the slab and meant less piling.”

Once the design was finalised work got under way on site in late 2006. As the project is located in the centre of an old historic town, the discovery of archaeological finds below the surface was not a surprise. Remnants of a 13th Century bridge’s abutments were unearthed during preliminary works. The findings were thoroughly surveyed by a team of archaeologists before being covered over for future generations.

The bridge remnants now lie beneath the main stage area and so there was a requirement for extensive foundation structures to transfer the loads from the fly tower columns over and away from the archaeological remains.

The majority of the brownfield site had already been cleared of its post-war industrial units before Willmott Dixon started work. A small scale site clearance was needed before 25m deep CFA piles and reinforced concrete ground beams were installed. Above this a suspended slab was cast with the main steel frame founded on the ground level pile caps.

Because of the theatre’s riverside location there is a danger of localised flooding and so the plans had to take this into account. Planning conditions restricted any public areas below the level of the river’s flood wall, so the theatre’s ground floor only accommodates storage areas, some offices and the box office.

“The building is one floor higher than it would have been because of these restrictions,” explains Mr Davies. “The three levels above ground floor house all of the public facilities such as foyers, bars and performance areas.”

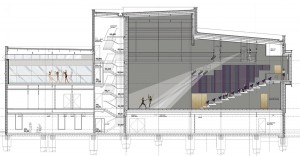

The main core of the structure houses a 638-seat main auditorium with three levels of seating, the smaller 250-seat Walker Theatre, a dance studio, a small exhibition space, green rooms and dressing rooms, a restaurant and a bar.

Most of the pubic amenities begin on the first floor, which provides access to the main auditorium stalls, as well as the Walker Theatre and Chapel Bar. Above this, two more floor levels provide access to the circle and the upper circle of the auditorium. Wide landings on the upper floors curve around the main auditorium, while also giving a sense of the scale of the building.

The main element of the project is the auditorium which is housed in a horseshoe-shaped drum and fronted by the three levels of seating. A series of 20m long x 1m deep trusses span this large open column free space with services running through the trusses’ depth. “There are a number of services in the main auditorium and the trusses also have to support lighting gantries and other technical equipment,” says Mr Dhanjal.

The auditorium’s perimeter has been constructed with a series of raking columns which support the roof trusses above. Cantilevering beams are hung from these columns to support the upper circles of seating as well as lighting gantries. Both circles have been formed with steel beams, cranked for the seating arrangement, and then infilled with timber. Another 18m long truss, tied into the roof truss steelwork, forms the stage’s proscenium arch.

Off-site construction played an important role in the construction of the auditorium’s fly tower. This steel framed core-like tower was erected by steelwork contractor Midland Steel Structures along with the rest of the frame. However the upper section of the tower houses the technical area where lighting and equipment are stored. This section consists of a large grid which was prefabricated at Midland’s yard and brought to site in three pieces. These were then bolted together on the ground before being lifted into place as one. The grid comprises a host of small steel sections and would have presented the erectors with a very time consuming task to assemble it on site.

Located in one corner of the fly tower’s footprint was an old substation which served the flood defence system for the surrounding area and relocation was not possible until the flooding season had ended. Unfortunately, construction was already underway so a phased works programme resulted in the 25m high tower being erected in two stages. Once the first phase was completed it had to be temporarily propped while the substation was moved allowing space for the rest of the tower to be erected.

As Theatre Severn houses a number of performance areas, acoustics as well as noise breakout was an important consideration in the design. The area around the theatre is a noise conservation area and to prevent sound escaping into the environs a pre cast concrete roof has been installed while heavy partitions divide the internal performance spaces.

Separating the main auditorium from the theatre’s foyer is a curved sloping zinc clad wall formed with cold rolled Metsec 200M12 studs in a twin frame configuration with three layers of 15mm plasterboard on each side for acoustic performance. “The two wall configuration is a cinema style partition,” explains Mr Dhanjal. The zinc rises above the glazed circulating areas to link with the auditorium side walls and is visible both internally and externally.

Meanwhile, the Walker Theatre has been noise insulated within a concrete box formed by two concrete slabs and a double row of columns with a 150mm cavity in between. This then isolates this performance space from the level below and the rest of the first floor. What makes this smaller theatre interesting is just how it was squeezed into the overall plan. “Because of height restrictions there wasn’t anywhere for the control room,” explains Curtins Project Engineer Paul Menzies. “The solution was to put a cantilever over one external elevation formed with a 15m long storey-high truss which houses the control room.”

Not all elements of historic interest were underground on this site. There is an old 19th Century Methodist Chapel which was recently used for a car tyre business. This building has been renovated and incorporated into the theatre. It now houses offices on the ground floor and fittingly the chapel bar on the first floor. A large 3D truss supports the curtain walling spanning over the chapel’s existing roof and connects into the theatre’s roof truss arrangement.

Now that the theatre is open, Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council has had time to reflect on the construction teams’ well designed project. A council spokesperson comments that the town has waited a long time for a new theatre and the building will help Shrewsbury develop as a ‘destination town’ drawing people from surrounding areas to enjoy the new cultural opportunities.