Projects and Features

Steel gives new heart to University campus

Working on a cramped central London university site to the most exacting of tolerances provided a challenge to the entire construction team, Everything was a perfect fit thanks to the steelwork contractor, as Margo Cole reports.

FACT FILE: The Hub

Main client: University of Westminster

Project value: £4.2M

Architect: GHM Rock Townsend

Structural engineer: whitbybird

Main contractor: Geoffrey Osborne

Steelwork contractor: Graham Wood Structural

Steel tonnage: 100t

The University of Westminster Cavendish campus, sitting in the shadow of London’s BT Tower, was a tight grouping of buildings dating from the 1970s but for the last three years it has been undergoing major redevelopment.The latest – and last – element of the redevelopment is a £4.2M project to build ‘The Hub’.

The Hub has been designed as a central link between buildings and to provide a heart to the campus; the architect’s initial thoughts for the building sprung from drawing a heart in the middle of the existing buildings linked to a new entrance.

Although The Hub was always part of the redevelopment plan, the first priority for the University was to upgrade its teaching facilities. This was achieved last year with the completion of a new £20M nine storey block on the Clipstone Street side of the site. However, the completion of that building – a replacement for a 1970s two storey structure – effectively hemmed in the area in which The Hub was to be built, so all the main structural elements of the complex had to be lifted over the newly completed building.

The Hub is being partially constructed by main contractor Osborne in the space left by demolishing an old concrete framed structure that housed an engineering laboratory.

The Hub is really two buildings: the main Hub building, which consists of two floors above ground and two below; and a “Pavilion” building, linked to the main building, which is a single storey structure built on an unused – and neglected – roof terrace.

The smaller Pavilion building has been designed as a “flexible” open plan space that could be used for anything from end of year shows to a café. It will be fully glazed – with exposed steelwork – and will open out onto a decked roof terrace.

The open plan nature of the building is reflected in the steel frame, which consists of vierendeel trusses around the perimeter, bearing on 244mm diameter circular columns. Cross beams made of 305 x 165 x 46 universal beam sections span the 6.65m between the trusses on the two long elevations. Above this frame is a sedum roof supported by timber joists at 400mm centres.

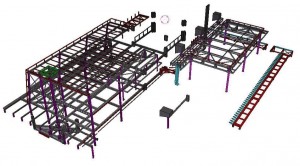

Wire frame model of the main Hub building showing the lift area with bracing taking loads onto the new transfer beam

Individual resin anchored plates were fabricated for the connections between the new steel and the existing lecture theatre columns

To build the main Hub building, the roof and columns of the engineering lab were demolished down to the lower ground floor level, leaving the foundations and basement, which houses a car park. The new three-storey Hub building has been built around a steel frame installed by steelwork contractor Graham Wood Structural that makes use of these original foundations. “By taking advantage of steel as a lightweight material we have managed to add an extra storey without having to strengthen the foundations,” explains Ali Abood, design engineer with structural consultant whitbybird.

Although the weight of the steelwork is not a crucial factor in the loads being transferred into the old foundations, concrete in the Holorib composite floors is. The designer specified lightweight aggregate for the 130mm thick slabs to ensure the weight stayed within allowable limits.

The structural steel frame of the Hub building sticks mainly to the 7m x 7m grid of the original concrete frame, so that the columns will bear directly onto the existing basement frame where possible. Beam and column sizes vary, but at first floor level most of the main columns are 203 x 203 sections, and the beams 254 x 254 universal column sections.

Adding an extra storey takes the height of the new building to the underside of the University’s main lecture theatre, with the soffit of the lecture theatre providing the roof for part of the Hub. Like many similar facilities, the theatre was designed with columns supporting the weight of the building, with the raked seating cantilevered over the rear set of columns. In the original design, the beams of the old lab building provided horizontal support for these columns. Once they had been demolished the contractor had to provide temporary props to these slender, reinforced concrete columns until the new structure was erected.

“Stability is the key to this building,” says Mr Abood. Although the new steel frame provides essential bracing for the columns supporting the lecture theatre, the concrete structure is also essential to the stability of the new steel frame.

“The architect really wanted The Hub to be a building with open spaces,” explains whitbybird director Martin Burden. “When you go through the entrance, you should be able to see all the way through. But because the architect didn’t want any walls anywhere, it has been very difficult to brace.”

There is only one possible location where bracing could go in, at the end of the building, where the three walls around the main lift have been braced with steel. Beneath these walls – at basement level – is a new 840mm steel transfer beam, which takes the load onto the original pile caps.

With no structural walls in the rest of the building, the only way to prevent the twist that would occur without bracing at the other end is to “grab” the four columns that support the lecture theatre, and now fall within the structure of the Hub’s main building.

“You can’t concentrate the loads, so we’ve designed connections that wrap around the columns,” says Mr Burden, “We want the load to go smoothly into the columns without exerting any additional moments.”

The old columns are cruciform in plan, and are extremely heavily reinforced. Fortunately, whitbybird has all the original reinforcement details for the original buildings, so could design connections that could avoid damaging any essential re-bar.

“We designed a series of plates that are resin-anchored to the existing columns,” explains Mr Burden. “Each plate is pre-drilled, but there are extra holes in case the hole lines up with the main steel. If it is in line with a link, that’s OK. They can cut through that.

“The connections have been designed so that the new steel is not clamping onto the columns, but ‘cuddling’ or grabbing them,” he continues.

When it came to erecting the steel, Graham Wood Structural fixed the connections plates first, and worked out from there, as there was absolutely no room for error on these connections.

The steelwork was procured while the demolition was underway. Even though whitbybird had access to the original design drawings, the design team could not be sure that they would find the as-built structure to be the same. The new steelwork connects to the existing campus buildings in 16 different places – including the four lecture theatre columns – so it was essential the steelwork fitted exactly.

“The whole building is surrounded by existing buildings and we have to get that building to be an exact fit,” explains Mr Abood. “When we started exposing things, plus or minus one millimetre could make a difference, so anything that was not as we planned it – even by a millimetre – we had to look at again.

“As we demolished, we had to confirm every bit, so there was a lot of pressure to get the information to the construction guys. To the credit of the steelwork contractor, everything fitted.”