Projects and Features

The New Black Book: Into the 21st Century with NSSS

Specifications: they aren’t glamorous, but they are important to our industry. They set standards and, along with drawings, act as a channel for the communication of design intent and consumer choice. Nobody knows better than a contractor that different things cost different amounts of money, so a clear and unambiguous definition of what’s wanted is in every party’s interest. Alistair Hughes reports.

Key issues for a typical steelwork contract include accuracy, protective treatment and weld quality assurance. In many of these respects, the well-advised client will moderate his demands within the bounds of what those on the receiving end of his specification are able to deliver without disproportionate effort and cost.

The idea of an industry standard specification is that this level of routine performance should be encapsulated in print, so that for the ordinary average project there is a clear understanding of what is expected and what to expect. That said, a ‘one size fits all’ philosophy would be doomed to failure – there will always be the projects, such as those which use steel aesthetically, for which it is legitimate, even essential, to set higher levels of performance. Not to mention the surprising number of ‘ordinary average’ projects which turn out to have some special feature or other!

One of the strengths of the National Structural Steelwork Specification for Building Construction (NSSS) since its inception is its dual format of printed ‘Black Book’ plus specially written ‘Project Specification’, the latter providing the vehicle for project-specific requirements as well as the contract- and siterelated information that tenderers need to know.

Updating the Black Book

When the time comes to update the Black Book, it is therefore the ‘Industry Standard’ provisions and procedures that are up for review. The BCSA, which gave birth to NSSS and remains its publisher, was mindful that its authority stems from consensus and accordingly gathered together a steering group representing all sides of the industry. The 4th edition that has now emerged owes much to its deliberations, ably chaired by Alan Pillinger of Bourne Steel.

The purpose of this article is to review what has changed, both to inform and to stimulate debate on a wider front. While the author was a member of the steering group, comments which follow are personal ones, from a specifier’s perspective, and carry no official status.

Welding

A document like the Black Book needs to be overhauled at intervals, if only to keep up with the unrelenting flow of new and revised standards from BSI. One feature on this occasion is that some of the new Euronorms are by no stretch of the imagination direct substitutes for the British Standards they replace.

The set of standards which deal with welding is a case in point. The subject is approached from a radically different perspective, not necessarily inferior to the traditional British approach but so different as to represent a culture change. The ‘European’ approach relies on the guiding hand of a welding specialist, employed by the contractor and given considerable freedom to set procedures, levels of inspection and response to test results.

Quite a few contractors operating in the UK steel buildings market have welding engineers on their staff, but rather more do not, so those of us on the other side of the contractual fence are torn between a long view that this will add value to the industry and a short term concern that old regimes must not be discarded before new ones can be relied upon.

Embracing BSEN 1011, instead of BS 5135, means embracing BSEN 719 and 729, which call for the involvement of ‘welding coordination personnel’. What does this rather inelegant title actually mean in practice?

Helpfully, annex A of EN 719 suggests that the European Welding Federation’s qualifications as Welding Engineer / Technologist / Specialist would do nicely. (Respectively, comprehensively expert / expert in specific area(s) of work / knowledgeable enough for simple work.) But these are not obligatory, as the BSI committee is at pains to point out in a ‘national annex NB’ which emphasizes that ‘the extent of education required by welding personnel should be decided by the manufacturing organization’.

Compilers of project specifications for work of any complexity might consider insisting upon a qualified welding engineer or equivalent. At the other end of the scale, BSEN 729-4 provides an escape route from all this coordination and control for the fabricator making pipe support brackets under a railway arch, say, whose ‘quality’ might be classed as ‘elementary’. So it’s as well to be aware that BSEN 729 subdivides – the other classifications, more relevant to our field of endeavour, are ‘comprehensive’ (BSEN 729-2) and ‘standard’ (BSEN 729-3).

Weld inspection

Even without the European dimension, approaches to weld inspection gave rise to much debate in the steering group. There was some evidence that the old Table 1 (scope of inspection; now replaced by Table B) had not been working as well as might be desired, owing to uneven application and difficulties of interpretation.

One example is the contrast between the testing requirements for butt and fillet welds. While it is true that many fillet welds are small and relatively unimportant in structural terms, not all are. Any fillet sized above 8mm leg length is likely to be a multi-run weld with a serious structural function. The threshold for MPI examination has therefore been lowered from 20mm and over to 10mm and over, albeit with a testing rate of 10% compared with 20% or more for butt welds. This will reduce any temptation to detail quite large fillet welds where butt welds would be preferable.

Another difficulty in practice has been the differentiation between ‘connection’ and ‘member’ zones, a well-intended attempt to concentrate attention on the most important welds but commonly far from obvious at the time the member is presented for inspection in the workshop.

To simplify matters, this has been swept away in the fourth edition, but with a reminder that the old Table 1 Part C of the third edition has been published in BS 5950-2, so remains available for those who would prefer it. It could be invoked in the project specification. Alternatively, the zones for ‘focused’ testing could be highlighted on the drawings.

Testing

Some concern has been expressed that the new table will increase the amount of testing to be done, and there may be some projects which now fall within the scope of NDT but would hitherto have slipped through the net. Others take the view that the simpler definition of scope will compensate for the inclusion of medium-sized fillet welds which previously escaped MPI scrutiny. Certainly the intention has been to rebalance the testing regime rather than increase the total amount of money spent on it.

One idea that fell by the wayside, though some of us were quite keen on it, was to link the amount of weld testing to the contractor’s track record, which would be banded according to membership of the industry’s own third party QA scheme and fine-tuned on the evidence of continuing satisfactory production on the work of the project. Not all welders are equally capable, and steelwork contractors vary in the effort they devote to the maintenance of standards.

In principle, investment in quality – such as training the workforce, employing welding specialists, trialling procedures – should pay a visible dividend in the form of lower testing rates as well as the less tangible benefit of smoother production.

A further virtuous circle would be set up if contractors felt incentivated to move up the quality league, increasing standards all round. A draft was prepared in which testing rates were halved for membership of the appropriate category of the QA scheme, with the prospect of further reduction at the engineer’s discretion, given evidence of continuing satisfactory production. While few individuals expressed opposition to the principle, it was in the end feared that contractors outside the QA scheme would respond negatively to perceived undue pressure to join it.

All that has survived the political correctness is a paragraph in 5.5.1 which holds out the possibility of discretionary reduction, on the evidence of initial production and BSEN 729 quality records, without stating any percentage.

Acceptance procedures

A rather less contentious modernisation effort went into the procedures for what used to be known as approval but is now termed acceptance. It’s important, especially with delegation of design responsibility such as for simple connections, that design intent is realized in the completed structure.

Traditionally fabrication drawings were exchanged, in large numbers. But consulting engineers are interested in checking matters of principle, not every dimensional detail. Computer-prepared fabrication instructions make old-style paper drawings optional, but we do still need to see how those components connect in non-standard situations. This is reflected in the amended clauses of section 3, which also provide for the submission of calculations prepared by the contractor, something previous editions had been silent on.

Contractor experience led to the inclusion of 3.6.5 – lack of response equals acceptance, though the engineer will always be given a call to say that manufacture is going ahead.

Section 1

The comprehensive rearrangement of section 1 is a change which is presentational rather than substantive. Some users have in the past been confused by the way the checklists for the Project Specification appeared almost as if they were specification clauses themselves. Really they are addressed to the issuer of the specification, not its recipient. It is hoped that the new format makes this more obvious.

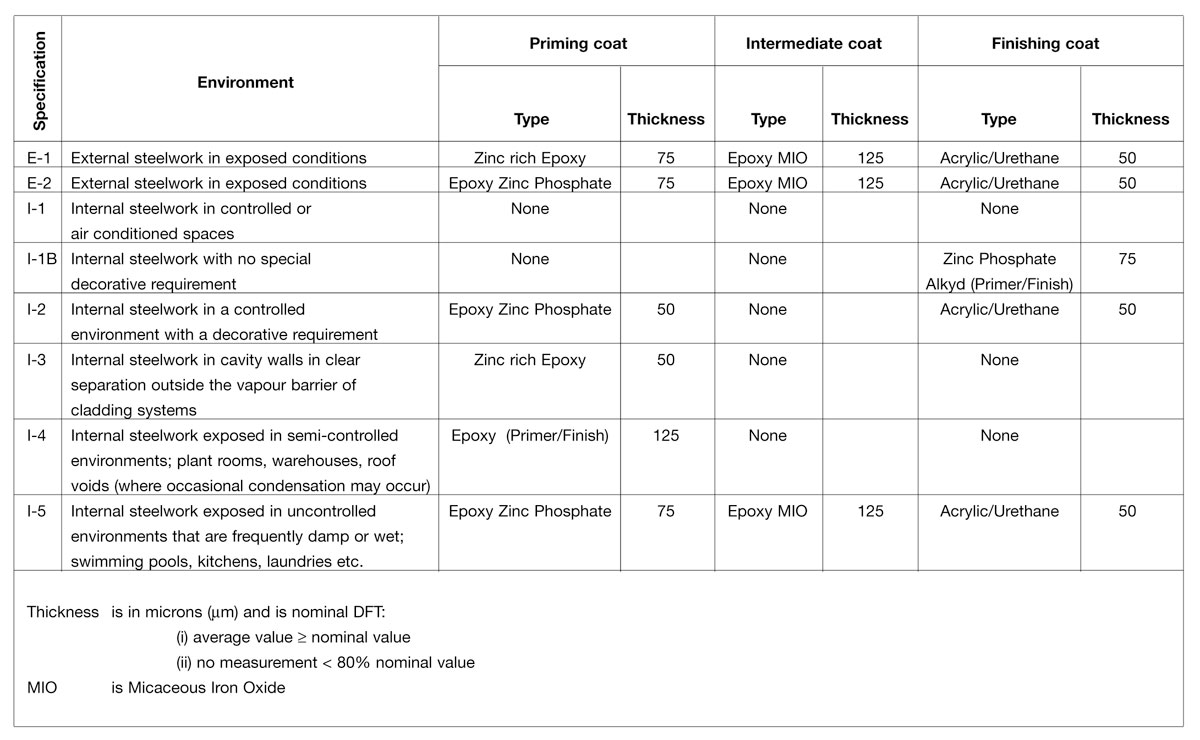

Paint systems

Newly published since the third edition are the industry standard paint system ‘recipes’ produced by CIRIA. Some of us on the steering committee argued for their inclusion in the Black Book, as a convenience to all concerned, and another step towards the goal of even slimmer Project Specifications.

We didn’t carry the day; perhaps the industry’s enthusiasm for these paint systems is less than total. The table that might have been is in the box headed ‘Specifications for Paint Coatings to Structural Steelwork’.

Hold times

Always controversial, because of the commercial imperative to keep production flowing, is the question of hold times, intended to ensure that any delayed-action hydrogen cracking happens before, not after, the weld area is inspected. The old rule’s ‘not less than 16 hours’ was all too often interpreted as ‘not more than 16 hours’, even when the circumstances (and BS 5135) demanded a longer wait.

The new Table A presents a graduated approach, according to thickness (combined thickness of the parts) and parent material CEV. It highlights the importance of specialist expertise where one or both is high. It will be interesting to see how this is received in practice.

Of course the fundamental requirement of the specification remains that cracks are not permitted; one point of view is that the contractor should be trusted to do what it takes to avoid them. The philosophy of EN 1011, 719 etc may be taking us in that direction, but it would take a sustained improvement in track record to justify deemphasizing effective independent inspection.

Lamellar tearing

The quite distinct problem of lamellar tearing is mentioned, as something to avoid, in Table C.1, but nowhere in Section 2 is there any prompt to select high-Z material in at-risk situations such as cruciform joints. BS 5950-2 goes further by calling for testing for through thickness properties, as well as for laminations, where ‘shown on the project drawings’.

Since increasing Z-grade adds cost, the compiler of a project specification should be alert to this issue, though the same can be said of the recipient since the required grade is a function not only of design but also of welding procedure.

Accuracy

Accuracy clauses have been revisited but the changes are relatively minor. Watch out, however, for the increase in the permitted deviation of a column centreline from 5mm to 10mm. But this limit applies to every column, not just the first to be erected. The average client’s appetite for accuracy does not diminish as the frame progresses!

A new clause controls the alignment of crane rails viewed on plan (to within a millimetre). Another allows plus or minus 10mm on the actual (as opposed to theoretical) cantilever of metal deck over its edge beam. This is intended to avoid unacceptable cantilevers, especially where the ribs are parallel to the beam, but it does make life more complicated for the people fixing the sheet metal who must simultaneously respect a permitted deviation, 10mm perhaps, of the concrete slab outline from theoretical.

Incidentally, the permitted deviations given in 9.1.1 and 9.1.2 for floors and walls (that steelwork is connecting to) are back-to-back with the newly-arrived National Concrete Specification – though realists amongst us will not be holding our breath.

Other changes

What else has changed? We no longer test studs by bashing them with a hammer – we bend them over with a steel tube, and every shift starts with two trial studs. Punching limitations are relaxed; the thickness must still not exceed the hole diameter, or 30mm, but the subgrade-related thickness restrictions disappear.

Ordering our raw material needs a little care these days. While its predecessor, BS 4360, actually had the word ‘weldable’ in its title, BSEN 10025 (etc) operates a ‘caveat emptor’ policy. To ensure that what is delivered is weldable, Table 2.1 now carries a note calling for invocation of option 5 (controlling CEV) and/or option 6 (ladle analysis). Clause 2.4 requires the manufacturer’s test certificates to be available, in any event.

In future, all weld procedures under the auspices of NSSS should either be for a CEV limit (e g 0.4 for S275 and 0.45 for S355, not exceeding 40mm thick) or be formulated to suit the chemical composition of the actual pieces of steel being joined. If this impacts on some downmarket importers and their customers, so much the better.

And the future?

Reading between the lines so far you may have gathered that the business of consensus can be hard work. Nevertheless we who were involved believe that positive progress has been registered on many fronts, and hope that this view will be shared by users of the fourth edition. It’s intriguing to speculate on what will be different in the fifth edition, if there is one – in theory BS 5950-2 (which has much in common with NSSS 3rd edition) and its very different European counterpart, EN 1090, are being lined up to replace it.

Maybe one day, but in the meantime a convenient, up to date and sensibly priced Black Book remains available. It has been the specification of choice since its launch in 1989. Keeping it that way is up to us!

The Fourth Edition NSSS is available from BCSA, price £20 inclusive of postage and packing.

New Black Book, New Grey Book

The Commentary which partners the Black Book aims to be a user-friendly guide to its application, with background information and interpretation which would be out of place in the Black Book itself, which has to be concise and legalistic. The Grey Book is a valuable reference for people preparing a project specification to cover special requirements which are, by definition, outside the scope of the Black Book.

Dick Stainsby, on whose desktop every word and diagram of every edition of NSSS has taken shape, authored the original Commentary. Along with Roger Pope, he has embarked on its revision. Their target date for publication of the new edition Grey Book is the end of 2002.

This will be Dick’s swansong and it is fitting to acknowledge the immense personal contribution he has made towards everything that the industry has achieved in the specifications arena.

Alastair Hughes is an Associate with Arup and a member of the Steering Group for the revision of NSSS.